The cost of living crisis has led to an explosion in the fast fashion industry. Buying cheap, low-quality clothes allows people to update their wardrobes regularly at a modest cost. But this comes at the expense of both the environment and the wellbeing of garment workers in developing countries.

Many people in the UK are struggling to make ends meet. The cost of living crisis – together with a decade of cuts to public service investment, poor economic growth and a weak labour market – means that households up and down the country are feeling the squeeze (The Conversation, 2025). This makes cheap clothing – or ‘fast fashion’ – appealing to many consumers. But over the longer term, is this sector beneficial to the global economy and wider society, including consumers and workers?

At the surface level, economic growth, including fashion sales and profit generation, improves prosperity. Around 300 million people are currently employed in the fashion industry and its associated supply chains, with the sector boasting global revenues of $1.55 trillion in 2021 (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019; Fashion United, 2025). This is projected to increase to around $2 trillion by 2026.

But probing more deeply into discount fashion culture suggests that the industry is one where the benefits of profit are highly imbalanced. The fast fashion business model is built on the exploitation of both the environment and people, creating wider negative economic implications (or ‘externalities’) across a number of dimensions.

- First, the speed of production and consumption are staggering. The Chinese clothes-maker Shein makes 6,000 new styles available to buy daily (Earth Day, 2022).

- Second, fashion is related closely to social capital and belonging: people want to present themselves as stylish and fashionable to avoid being judged by other people (McNeil, 2018).

- Third, people do not want to be seen in the same outfit: with images on social media counting as being ‘seen’, many younger women consumers wear a garment only once (Weber and Ritch, 2023). Cheap supply and the pressure to keep up with trends have generated an alarming throwaway culture.

To get a better understanding of the impact of these traits, it is useful to consider fast fashion from the perspective of sustainability (as defined by World Commission on Environment and Development). Our Common Future, the Brundtland report, offers insights into three interconnected systems – economy, environment and society – and argues that all three branches should be given equal importance: if one is compromised, ultimately this will affect the others (Brundtland, 1998).

For example, over half of global GDP is reliant on nature-based resources. If the planet’s eco-systems fail, then this will hit business operations and employment (UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme, 2025). Examining the wider consequences of cheap garments shines light on the role of discount culture in facilitating such a ‘race to the bottom’ for both labour markets and the environment, ultimately eroding economic prosperity.

How has the fashion industry changed?

The prices of clothes, shoes and accessories in most advanced economies (like the UK) have been decreasing over the last few decades. This trend has been propelled by the outsourcing of production overseas, where labour costs are cheaper. While the price of individual garments has fallen for consumers, to ensure profit generation for fast fashion retailers, the cycle of fashion trends has accelerated (keeping people buying items regularly).

Traditionally, new seasonal styles and colour palettes were presented by fashion designers at the biannual global ‘fashion weeks’ in London, Milan, New York and Paris, and this trickled down into the high street.

But the industry now moves much faster. Globalised supply chains and high-tech production management systems have enabled new styles and designs to become available to purchase weekly.

This fast fashion is heavily marketed, with time-bound tactics deployed to entice impulsive and frequent consumption (Ritch and Siddiqui, 2023). For example, checkout timer clocks count down a limited time to make the purchase; limited-time offers for additional savings (like free delivery) prompt urgent purchases to save costs; and declared product scarcity (such as ‘only two items left’ or ‘this item is in two other people’s baskets’) generate a sense of panic to spend ‘now’. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) argues that these tactics create a false sense of urgency in order to pressurise consumers into making hasty decisions (CMA, 2023).

Quick and frequent sales are the lifeblood of fast fashion – and the system works. Marketing designed to encourage frequent and impulsive consumption, together with low pricing to reduce the main barrier of affording new items (cost), has meant that sales of fast fashion products have grown significantly over the past few decades (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 also indicates how our use of individual items of clothing has reduced. There are two main reasons for this. First, fast fashion production cuts corners to reduce manufacturing costs, so materials are thinner, and pattern cutting and construction are simplified to ensure that items are available to the consumer quickly and cheaply.

This means that the garments don’t last long; the materials don’t wash well; holes appear in the material after a few wears; and seams often burst or become squint, meaning that the clothes end up not fitting well (WWF, World Wide Fund for Nature, 2025; Ritch, 2020). For the consumer, with a low investment in the garment, it is cheaper to throw the garment away than to repair it.

Figure 1: Growth of clothing sales and decline in clothing use, 2000-2015

Source: Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2021

Note: Indexing reflects 2000 values, sales and GDP start at 100; utilisation begins at 200.

Second, the continuous nudge from fashion marketing, where new styles are relentlessly promoted via a range of media types, encourages consumers to keep up with the latest looks. As such, regularly buying cheap items has become normal.

This issue is particularly pronounced in the UK: Brits spent the third largest amount of money in the world on clothing (after only the United States and China), despite the UK being ranked 21st for population size (Choudhary, 2023).

What are the environmental impacts of fast fashion?

Cutting corners in production affects both the environment and the people employed across fashion supply chains. Starting with the climate, the United Nations (UN) claims that the fast fashion industry is the second biggest polluting industry after aviation (UN, 2019). Not only are the manufacturers of cheap garments heavily dependent on scarce resources, but they also produce items that are made with little expectation for longevity, making clothes that are often quickly discarded to landfill.

All of this exacerbates the climate emergency (Harrabin, 2018). Fast fashion production processes can also lead to chemical residue contaminating both water and food sources, as well as the depletion of soil fertility.

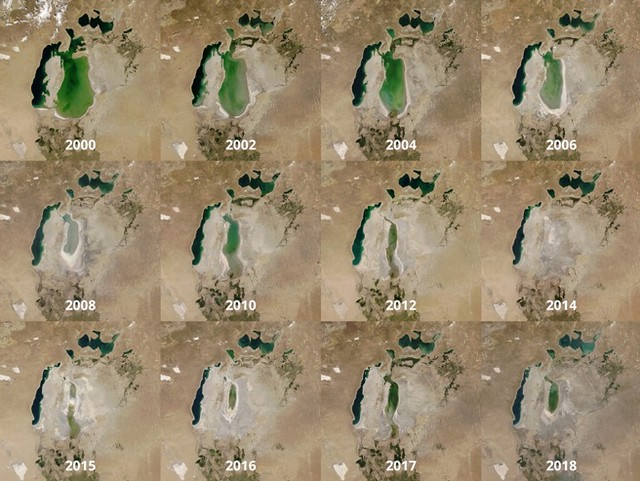

To grasp the scale of this issue, consider how scarce resources have been depleted from the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan is the second biggest cotton producer after the United States. But cotton production is highly water-intensive. So, to increase the volume of the crop produced, in the 1960s, the Soviet Union began diverting the Aral Sea’s main inflowing rivers – the Amu Darya originating from the Pamir Mountains and the Syr Darya from the Tien Shan mountain ranges – for irrigation purposes (Earth Org, 2024).

This had catastrophic consequences. Figure 2 captures the reduction of the Aral Sea from 2000 to 2018. After just 18 years, half of the sea had vanished (Chen, 2018). This affected the region’s economy, as fishing was one of the main sources of income for many local Uzbekistani people (Myers, 2020). The change in the physical environment has also reduced the air quality, leading to an increase in respiratory disease and cancer diagnoses in the surrounding area (Crighton et al, 2018).

Figure 2: Depletion of Aral Sea, 2000-2018

Source: Flickr, picture posted by NASA/Earth Observatory. Video version available here.

But the disposal of fast fashion products is also a problem (Gray, 2024). Cheap garments often begin their short lifecycle in factories in the global south, where labour is cheap and working conditions are often extremely tough. As these items are made cheaply, they can only be worn for a limited number of times (before falling apart).

In many cases, these clothes end up in landfill. Either that or they are donated to charity shops or clothes banks (although in the UK, consumers do not buy nearly enough second-hand garments to mitigate what is thrown away). In either case, when consumers in the global north dispose of unwanted pieces, they still exist somewhere on the planet – most often in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, contributing to local pollution of the land and sea (Britten, 2024).

What are working conditions like in the fast fashion industry?

Low pay is rife within the fast fashion industry. Modern-day slavery has also been alleged in many instances over the past few decades. Outsourcing garment manufacture to reduce production costs is said to result in textiles workers being exploited through long working hours, low pay and inhumane working conditions that breach health and safety regulations (Adegeest, 2024). These concerning outcomes suggest an unsustainable business model, and one that is widening wealth inequalities around the world.

Specific allegations of exploitation include the widely reported Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh two years ago (BBC, 2023). This tragedy led to widespread condemnation of the poor treatment of workers across the industry, with fashion firms agreeing to manage production practices better in the future. But since the accident, alarming allegations continue to be made (Clean Clothes, 2024).

This issue is not limited to countries in South Asia. Factories in the UK have been found operating precarious employment contracts, offering wages as low as £4 per hour (Ball, 2024). The current minimum wage is £11.44 for those over 21 years of age, with £12.60 considered to be the reasonable national living wage (Living Wage, 2025). Clearly, the wages offered by certain garment producers are exploitative and illegal.

Erica Charles (Glasgow Caledonian University) has conducted research on UK garment workers’ experiences in factories, and this film captures how tough employment conditions and poor wages affect these people’s lives.

In contrast, the owners of fast fashion retailers are among some of the richest people in the world. Amancio Ortega (the owner of Zara) is the eighth wealthiest person in the world. The Walmart family is placed tenth (Forbes, 2025). The owners of Primark increased their wealth by over £2.5 billion last year – all while garment workers struggle to feed their families.

The false economy of discount culture

Unfortunately, these alarming trends appear to be running in one direction only. While the fast fashion business model is highly lucrative, profit margins per garment have shrunk. This means that the volume of sales needed to turn a profit is constantly increasing. In some parts of the market, fast fashion has been replaced by ‘ultra-fast fashion’, with new discount retailers such as Shein and Temu further accelerating the race to the bottom (BBC News, 2025).

Economic growth at any cost does not foster long-term sustainability. Much of the global economy (including the fashion industry) requires the extraction and consumption of natural resources. But the continued depletion of eco-systems could reduce GDP, particularly for economies in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (see Figure 3).

In addition, low pay and insecure work contracts have contributed to in-work poverty across the fashion industry (McKnight et al, 2016). Over the past few years, there has been increased reliance on food banks in the UK, linked to the cost of living crisis and the stagnating economy post-pandemic (Francis-Devine et al, 2024). It is not only garment workers who are facing tough conditions: also struggling are the couriers who deliver online fashion purchases and the warehouse workers who experience strict targets monitoring their productivity (Butler, 2025).

Figure 3: Change in 2030 real GDP under partial eco-system collapse, by region

Source: World Economic Forum, 2021

Note: bar size is proportional to the estimated population in 2030.

How can we access fashion that benefits the wider economy and contributes to sustainable growth?

It is unrealistic to suggest that consumers should stop buying fast fashion altogether, given the cost of living crisis. But there are ways in which consumers can make better choices. These could include:

- Adopting a more mindful approach to fashion by purchasing fewer items and making quality a priority; and considering how garments are made, the duration of their use, and responsible disposal methods. Options include ‘upcycling’ (transforming garments into new items) or ‘downcycling’ (such using strips of material for household cleaning cloths).

- Evaluating the ‘cost-per-wear’ of items (Fashion United, 2024). Assessing how often a piece will be worn or used can lead to better long-term investments. High-quality materials and careful assembly can improve the fit, comfort and style of clothing.

- Engaging with redistribution markets like Vinted and Depop or exploring charity shops. These avenues provide access to well-made items and offer opportunities to recoup some expenses, contributing to the circular economy and maximising existing resources.

- Considering renting clothes and accessories (Murray and May, 2024). Renting allows for regular wardrobe updates in a sustainable and affordable manner, often providing access to designer items that would otherwise be out of reach.

- Participating in repair and upcycling workshops to maximise the potential of existing clothing. These workshops, increasingly available across the UK, offer valuable skills and promote a more individual and creative approach to fashion. Engaging in the creative process of fashion can also enhance the emotional connection with clothing and highlight the joy and fun that fashion can bring (Byrne, 2025; University of Dundee, 2025).

Where can I find out more?

- Towards a circular economy: Business rationale for an accelerated transition: article published in 2015 by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

- Earth Logic: Fashion Action Research Plan: book by Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham published in 2019 (free e-book available to download).

- Driven to Shop: The Psychology of Fast Fashion: article by Audrey Lin, published in 2022 by Earthday.org.

Who are experts on this question?

- Kate Fletcher

- Patsy Perry

- Helen Goworek

- Elaine Ritch