Weather can have a significant impact on agricultural production. Changes in climate and increases in extreme weather events exacerbate this, leaving poor households in rural areas particularly vulnerable.

Global poverty is mostly a rural phenomenon. According to the World Bank, nearly three-quarters of the 650 million people around the world living in extreme poverty are outside towns and cities. The majority are in countries located between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, where two-thirds of the population rely on low-productivity small-scale farming.

For these households, weather can have a big impact on production. And abrupt changes in climate make them even more vulnerable.

How is climate affecting agricultural output?

Climate change is usually associated with an increase in the incidence and severity of extreme events, such as wildfires, cyclones, droughts and floods. These can ruin agricultural production, directly hurting rural livelihoods (Carleton and Hsiang, 2016). Other changes – such as fluctuations in precipitation or global warming – are harder to notice but can still have devastating effects on rural incomes.

Global warming refers to a rise in average temperatures. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human activities have already increased average global temperatures by around 1°C compared with pre-industrial levels (IPCC, 2021).

For crop growth in agricultural production, heat can be good, but only up to a point. Plant science shows that exposure to very high temperatures decreases crop productivity. For example, temperatures above around 30°C are deemed to be harmful to corn (Schlenker and Roberts, 2009).

A small increase in temperatures may not sound too bad, but that’s why global warming is like a silent killer: average temperatures rise not because every day is a little hotter, but because the number of extremely hot days increases. More frequent and longer heatwaves mean that crops are exposed to harmful temperatures and, thus, agricultural productivity decreases (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Change in productivity at different temperatures

Source: Aragón et al, 2021 Note: Data from small household farms in Peru show a drop in farm productivity for larger temperature realisations

Figure 2: Effects of temperature on wheat yields

Source: Shew et al, 2020 Note: Data from South Africa show a sharp reduction in wheat yields when temperatures are above 30°C.

The consensus among scientists is that the predicted increase in hot days will happen in countries between the tropics, where most rural poor reside. Current international efforts are focusing on containing the rise to about 1.5°C by the end of the century (IPCC, 2018). But this objective may well be beyond reach in many places. For example, Figure 3 shows that every year between 2015 and 2020, average temperatures in Africa have already exceeded historical averages by more than one degree.

Figure 3: Average temperatures for Africa, 1880-2021 (in excess of historical averages)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) taking place in Glasgow in November 2021 will discuss progress and further measures to meet the target. The strategy includes moving from fossil fuels to cleaner sources of power to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that drive global warming. Protecting forests and accelerating the transition towards sustainable agricultural practices will also be important.

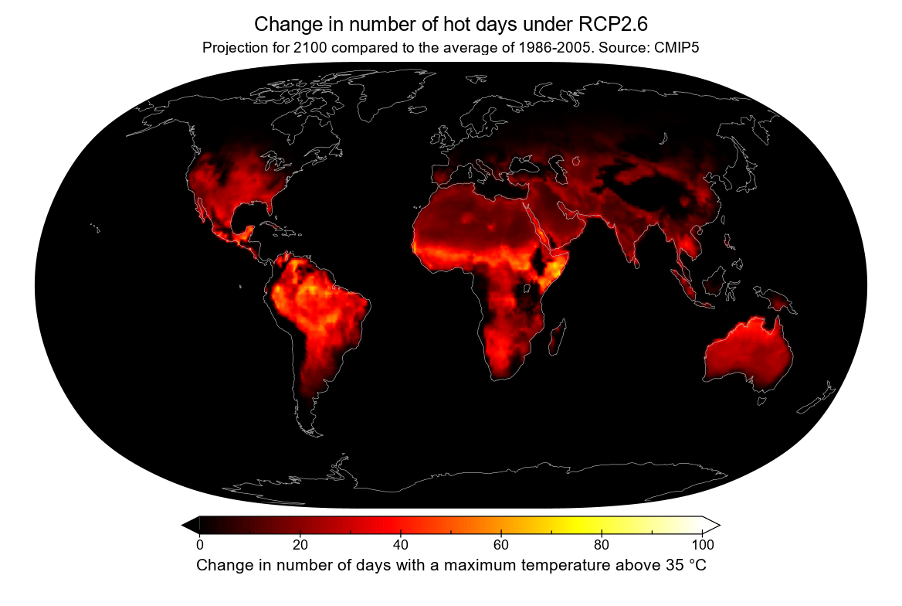

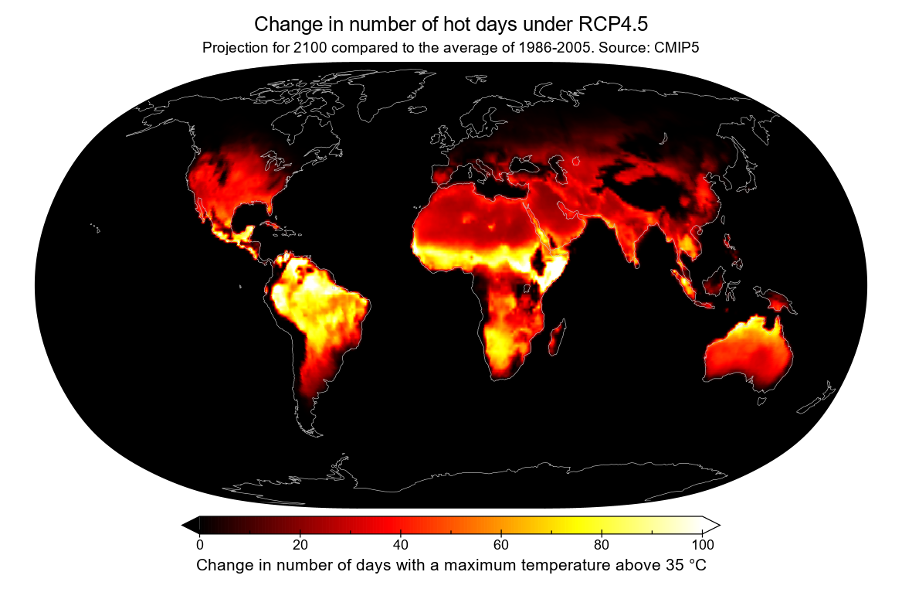

Yet even if this goal is achieved, some regions of the world are still expected to experience up to 70 additional days of extremely hot weather each year by the end of the century (see Figure 4). This implies that climate change’s direct effect on rural livelihoods and poverty is not expected to go away any time soon.

Figure 4: Projected changes in the number of hot days under two different scenarios of global warming

Source: CMIP5 Note: Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6 corresponds to a radiative forcing of 2.6W/m², equivalent to a warming of 1.5-2°C; RCP4.5 corresponds to a radiative forcing of 4.5W/m², equivalent to a 2-3°C warming.

Research in economics and other disciplines shows evidence of lower productivity due to increased heat during the growing seasons all around the world, in low, middle and high-income countries. There is also evidence that farmers, particularly those in low-income countries, are responding, by switching crops, changing productive practices or even moving away from agriculture entirely (Aragon et al, 2021; Colmer, forthcoming; Taraz, 2018).

But responding to, and coping with, these shocks becomes an uphill struggle when the economic environment presents poorly developed input and output markets, lack of insurance or finance, and institutions that prevent the reallocation of resources, such as land or labour, within and across sectors.

For example, in many places, farmers do not have secure property over the land they work, either because there is no formal record of ownership or because they are using communal lands. For example, in Uganda, around 80% of the land is under customary arrangements, rather than formal titles. In these cases, farmers may not be able to sell the land and move elsewhere. Further, even if they could move, they may struggle to find employment as in some countries – even large ones like Nigeria or Ethiopia – fewer than 20% of workers work for a wage (Rud and Trapeznikova, 2021).

Some countries or regions may even benefit from a warmer or wetter climate (Deschenes and Greenstone, 2007). For example, evidence from Peru shows that farmers on the coast (a dry and warm region) would suffer from projected changes in temperatures, while farmers in the highlands (which are cold and wet) would slightly benefit from a few more hot days during the growing season (Aragon et al, 2021).

Nevertheless, agricultural output overall still suffers when exposed to extreme weather events. Together with effects on related sectors, such as livestock or fisheries, and other transformations, such as population growth and urbanisation, climate change is also threatening food security in non-rural areas of low-income countries.

That is why it is so important that international efforts focus on building resilience among farmers, to manage and reduce exposure to risks and to reduce vulnerability.

Scientists, economists and researchers from other disciplines around the world have identified instruments that can improve the outlook of the rural poor, such as insurance that is linked to weather effects, improving access to finance, technical assistance and access to new technologies and products, such as heat- or flood-resistant crops or infrastructure, such as irrigation.

The fight against poverty around the world cannot be separated from action and policies aimed at reducing global warming and from investments to cope with changes in the climate that may well be irreversible.

Where can I find out more?

- BBC: Six graphics that explain climate change

- Measuring the real-world costs of climate change: Climate Impact Lab

- The World Bank’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal to explore historical data and climate projections for regions and countries

- Agriculture and Climate change: European Environmental Agency

- Global Warming of 1.5°C: Summary for policy-makers of the IPCC’s 2018 Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change

- Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis: The IPCC’s 2021 report

- When exposed to harmful high temperatures, subsistence farmers increase their use of land and change their crop mix to mitigate the decline in output

Who are experts on this question?

- Tamma Carleton

- Solomon Hsiang

- Wolfram Schlenker

- Michael Greenstone

- Vis Taraz

- Olivier Deschenes