Northern Irish voters go to the polls on 5 May to elect 90 members to the nation’s legislative assembly. There are several major economic issues facing the next government, including skills, productivity, healthcare and the continuing challenge of Brexit.

Newsletter from 29 April 2022

Unlike the devolved legislative assemblies in Wales and Scotland, the Northern Ireland Assembly has power-sharing at its core. This means that unionists and nationalists both participate in governing the nation and that cross-community support from both groups is required for legislation to be passed. This arrangement is part of the Belfast or Good Friday Agreement – the 1998 deal that brought a cessation to the long period of violence and instability known as the Troubles.

But power-sharing has its downside. Without agreement from both sides of the sectarian divide, a government cannot be formed, and if one side withdraws its support, the whole government collapses. Since the Assembly’s inauguration in 1999, Northern Ireland has been without a government for nearly eight of the past 22 years. Most recently, the Assembly was suspended from 9 January 2017 to 11 January 2020.

The Northern Ireland Protocol

Brexit has contributed to political instability and tensions in Northern Ireland. The UK’s exit from the European Union (EU) meant that a border check for goods either needed to be on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland or between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

The latter was chosen, and the Northern Ireland Protocol came into effect in early 2021. The Protocol means that goods coming from Great Britain into Northern Ireland are checked to ensure compliance with the tariff and non-tariff aspects of the EU’s single market and customs union.

The implementation of the Protocol has caused unionist political parties to become vexed about Northern Ireland ’s constitutional position within the UK and is playing a major role in the upcoming election. The main slogan of one unionist party is ‘No Sea Border’. Unionist parties may also be unwilling to form a government with the Protocol in its current guise.

Leaving aside the constitutional question, Esmond Birnie (Ulster University) in his Economics Observatory article this week examines the economic impact of the Protocol. For me, there are two main takeaways from his piece. First, we need much better data to assess the impact of the Protocol and to establish the winners and losers from it. A careful and detailed economic appraisal may help to allay wider concerns. Second, there are several policy options available that could help to reduce the regulatory burden of the Protocol.

Fixing the NHS

The NHS in Northern Ireland is in a mess. Ciaran O’Neill (Queen's University Belfast) in his piece highlights the extent of the problem. Prior to the pandemic, the number of people waiting over a year for a consultant-led outpatient appointment was 100 times greater in Northern Ireland than in England, despite England’s population being 29 times larger than that of Northern Ireland.

The solutions to fixing the NHS in Northern Ireland have been long known – rationalisation of the hospital sector, better workforce planning, long-term budget setting and sustained investment. So, why haven’t these things happened? Political instability and the design of Northern Ireland’s political institutions mean that politicians have not had a long-term vision for the NHS and do not have the incentives to reform it.

Growing the economy

Productivity is central to growing the Northern Irish economy and it needs to take centre stage in the next government's economic policy. The nation’s productivity is almost 20% lower than the UK average. What needs to be done to close this substantial gap?

David Jordan (Queen's University Belfast) in his article on skills shows how Northern Ireland’s attainment gap and brain drain affect the province’s productivity (Figure 1). The incoming government will need to make this skills deficit one of its top priorities. This will require difficult decisions about inefficient and divided school systems, investment in lifelong learning and improved funding for further and higher education.

Figure 1: Educational attainment of individuals aged 16-64, in 2020

Source: Nomis, ONS Annual Population Survey

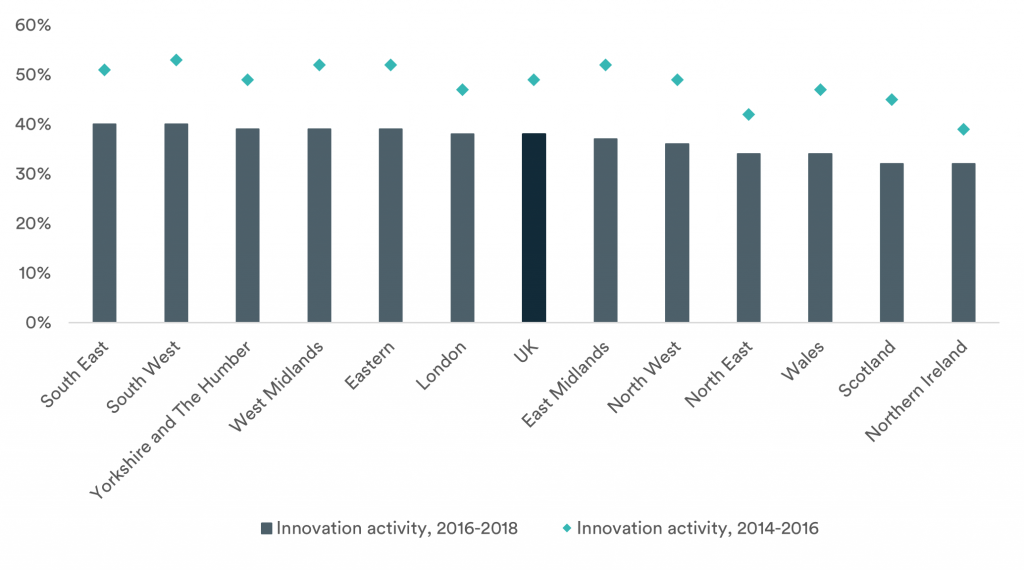

In addition to skills, innovation activity is a major driver of productivity. As Karen Bonner (Ulster University) shows in her article, Northern Ireland performs poorly on business innovation activity compared with other UK regions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage of innovation-active businesses by UK region, 2014-16 and 2016-18

Source: NISRA

Nevertheless, she also shows that Northern Ireland has an advanced innovation ecosystem with high levels of collaboration between innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The incoming government will need to build on and facilitate this. Investment in skills, lifelong learning and higher education will again be important to help the innovation ecosystem to flourish.

Political instability is also playing a role in holding back productivity growth. Instability has meant that the long-term policies that would enhance Northern Ireland’s abysmal productivity performance and lay the foundation for a prosperous economy have been neglected.

The inherent instability of the Northern Ireland Assembly creates uncertainty for businesses – something they seriously dislike. This, in turn, means reduced investment by businesses (Bernanke, 1983; Bloom, 2014), higher costs of capital (Pástor and Veronesi, 2013), reduced business formation (Dutta et al, 2013) and the diversion of entrepreneurs into other activities (Baumol, 1996).

Even if political instability can be addressed, politicians in Northern Ireland have no incentive to grow the province’s economy because they have no skin in the game. The Northern Ireland Assembly gets a block grant from Westminster and simply allocates it among the various government departments. If fiscal powers were devolved, then politicians would have a strong incentive to grow the economy and the tax base.

A plea for stability

Political stability and well-designed political institutions are foundational for a successful economy. Politicians in Northern Ireland, Ireland, the EU and the rest of the UK need to make political stability their number one priority.

The political institutions created under the Good Friday Agreement need to be refreshed so that Northern Ireland’s government cannot be so easily collapsed when one community does not get their way. Alternatively, power could be handed over to publicly accountable technocrats to run public services such as health and education and skills. This may create a democratic deficit, but the health of Northern Ireland’s economy and its population may well warrant it.

More importantly, as highlighted in a video released by the Financial Times this week, political stability is of paramount importance for the youth and divided communities of Northern Ireland.