If the government decides to raise taxes after the pandemic, an alternative to taxes on work or spending could by a one-off wealth tax. A well-designed tax of this kind could raise significant revenue in a fair and efficient way without excessive administrative costs.

Despite recent positive news of the various effective vaccines, the Covid-19 recovery process is likely to be long and costly.

As the Office for Budget Responsibility’s recent report highlights, the economic damage is likely to be substantial. According to the report, even when the economy returns to its pre-crisis levels of unemployment and GDP, tax revenues are likely to fall short of spending by £20-30 billion.

Related video: Covid-19: Paying for the pandemic

The government has already signalled a preference not to return to the austerity of the past decade. Even before the pandemic there were plans to increase spending to ‘level up’ less well-off regions of the country.

Related question: #economicsfest: Where next for the UK’s ‘levelling up’ agenda?

This suggests that tax rises will be coming at some point. But a key question for policy-makers to address is where these tax rises should fall.

How much money could a wealth tax generate and who would pay it?

The conventional wisdom is that there are only three taxes that are effective when it comes to raising substantial fiscal revenue: income tax, national insurance contributions and VAT. But analysis in the final report of the Wealth Tax Commission shows the scale of revenues that could be raised by a one-off tax on assets.

The report suggests that a wealth tax could raise a substantial amount of revenue at relatively modest tax rates. For an annual wealth tax, a flat tax of 0.18% on wealth above £500,000 could generate £10 billion in revenue.

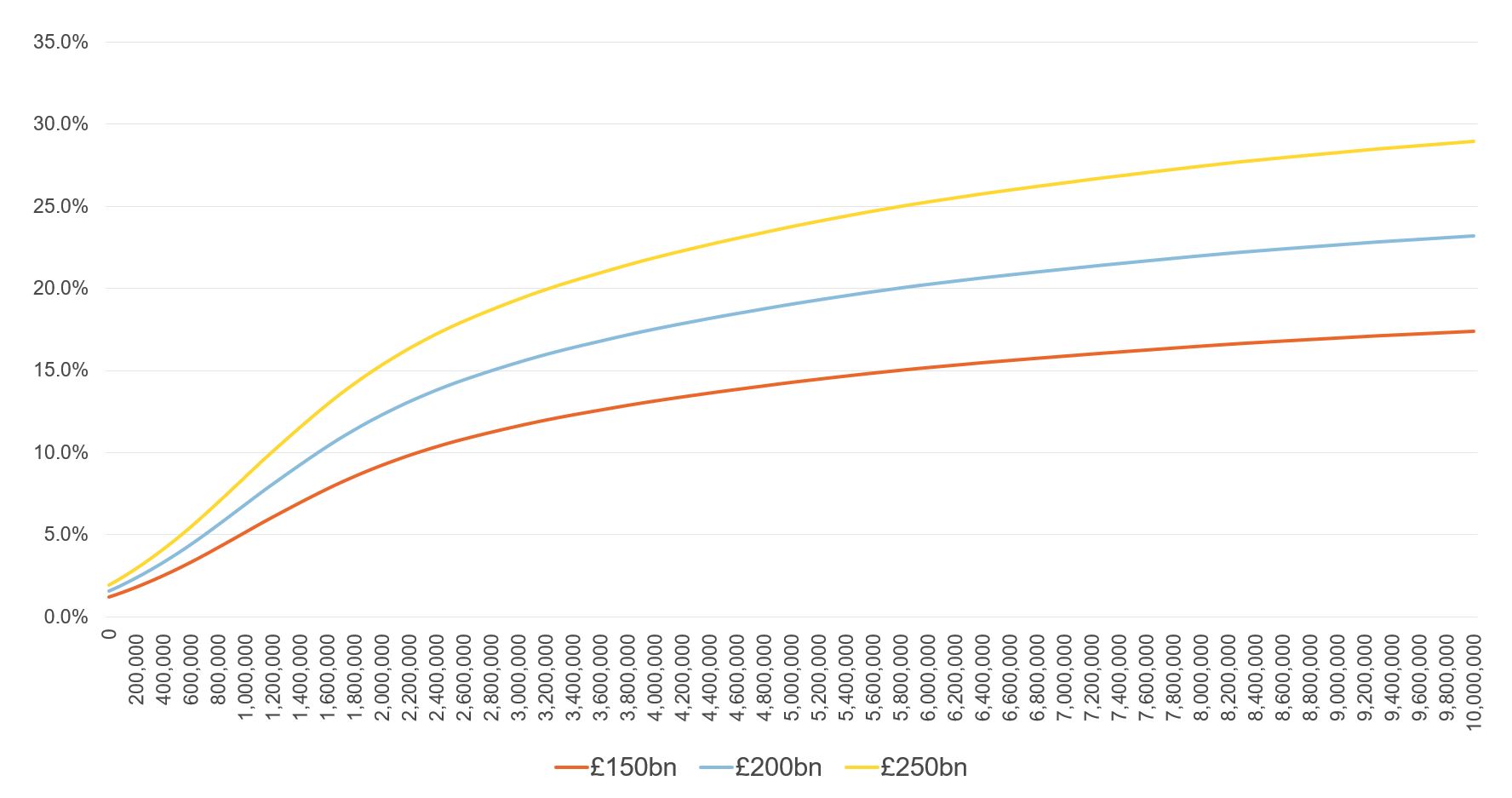

Alternatively, the government could introduce a one-off tax or ‘windfall tax’ on wealth. A one-off wealth tax charging a tax rate of 4.8% on wealth above £500,000 would generate £250 billion in revenue, before administrative costs. This would come at a total cost of £1.7 billion to the government, and £7.2 billion to the taxpayer (see Figure 1).

As a one-off event, it is possible to achieve a much higher ratio of revenue to cost than under an annual wealth tax. A higher threshold would reduce the administrative costs further, though achieving the same amount of revenue would necessitate higher rates.

Figure 1: Rate and thresholds generating different revenue targets from a one-off wealth tax, after administrative costs

Source: Advani et al (2020)

The advantage of a one-off wealth tax is that it would be closely linked to people’s ability to pay and does not discourage people from working. It would also be popular: in a survey of public attitudes commissioned as part of the report, a one-off wealth tax was the most preferred option for any tax rise – twice as popular as second place council tax.

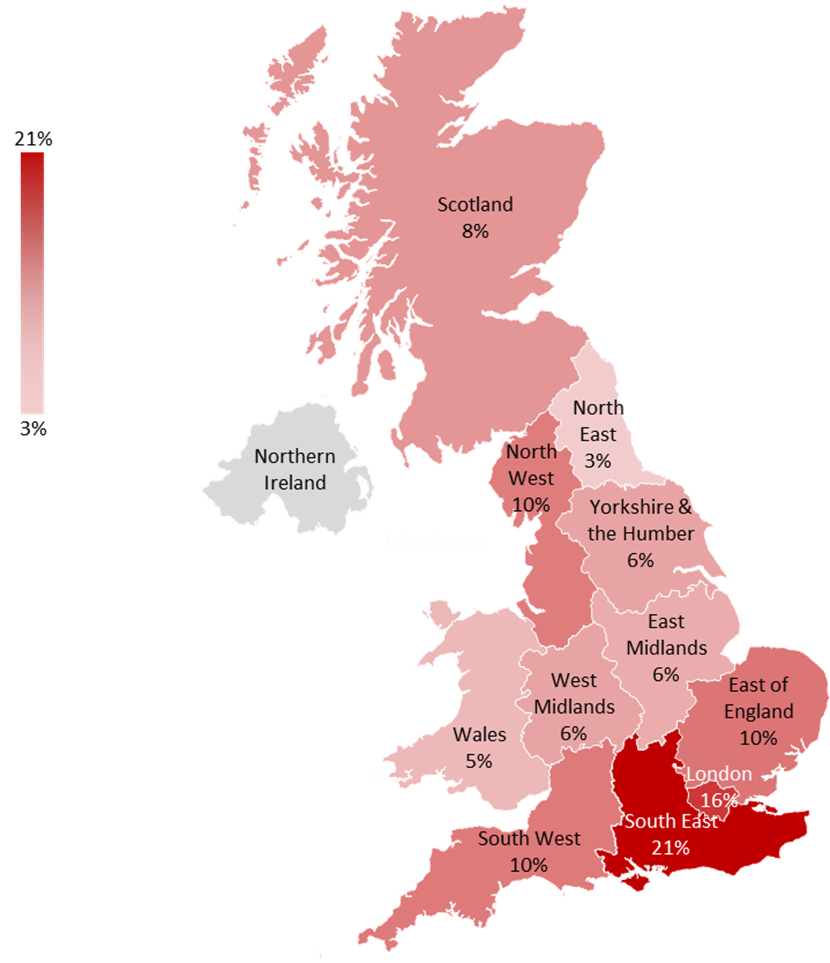

In either case, the majority of taxpayers would be of working age, with individuals aged 55-64 being the most heavily represented. According to the commission’s report, the population of taxpayers would be skewed toward men. Further, taxpayers would be concentrated in London and the South East (see Figure 2), with these regions accounting for 37% of all taxpayers under a wealth tax starting at £500,000.

Figure 2: Geographical distribution of taxpayers with a £500,000 exemption threshold

Source: Advani et al (2020)

How else could the government pay for the pandemic?

In order to meeting the mounting costs of Covid-19, the government could also raise revenue by reforming existing taxes on capital. This would, however, still come at a cost, and would not necessarily avoid the challenges imposed by a wealth tax. Options for reform include:

- Raising capital gains tax rates in line with income tax rates would raise an additional £12 billion, at no extra cost.

- Reforming inheritance tax to include pensions, and removing agricultural property relief and business property relief could raise an extra £1.3 billion, at an additional cost of £17 million per year.

- Revaluing properties for council tax, and taxing in proportion to property values at a fixed rate of 0.83% would raise an extra £17.6 billion at a one-off cost of £245 million.

- Bringing the tax rate on dividends in line with the tax on earned income would raise an additional £4.9 billion, at no extra cost.

Related question: Should the government be planning tax rises and public spending cuts?

How much would I pay?

The work of the Wealth Tax Commission shows that it is possible to raise money by taxing wealth. But there are still important political choices. Policy-makers need to discern where such a tax should start, and at what rates they should set it. Crucially, it remains to be decided whether the rates would be flat or progressive?

Administrative costs set some boundaries on these questions, but there remains a big political choice in who pays and how much. That is why, alongside the final report, the Wealth Tax Commission has launched a tax simulator, allowing the public to design their own wealth tax. This tool illustrates the different combination of tax regimes and how much they could raise as well as how much they would cost in terms of administration.

In any case, the introduction of a new tax brings with it political challenges for any government. The main policy issue is finding a way to generate a substantial amount of fiscal revenue without harming economic growth by discouraging work or creating additional constraints on financially vulnerable businesses.

The final report of the Wealth Tax Commission shows how, if designed carefully, a one-off tax on the richest in society could be an effective means in which to begin paying for the pandemic. Like most policies, however, such a tax will create winners and losers. Deciding who these winners and losers are – at least in terms of their tax bills – is a vital question for government to answer as they plan for economic recovery in 2021.

Where can I find out more?

- The Wealth Tax Commission website

- Revenue and distributional modelling for a wealth tax: Wealth Tax Commission evidence paper by Arun Advani, Helen Hughson and Hannah Tarrant.