People’s economic experience of Covid-19 depends partly on whether it is possible for them to work from home. Fewer jobs can be done at home in poorer countries, which means that workers are at risk of either losing their jobs or becoming exposed to the virus while at work.

The ability to work from home is an important factor in how people’s working lives have been affected by Covid-19 and the associated lockdown measures introduced to curb its spread.

In developing countries such as Brazil, people lower down the distribution of income are less likely to be able to do their job from home. The impossibility of switching to home working primarily affects the most vulnerable population and is forcing millions of low-qualified workers to continue to leave the house during the pandemic.

What does research say about home workers in the time of coronavirus?

The implementation of lockdown measures has been one of the most common strategies to reduce the movement of people and slow down the spread of coronavirus (Signorelli et al, 2020). To reduce the negative effects on the labour market of these measures, many governments are encouraging their residents to work from home.

A recent policy brief by the International Labour Organization (ILO) indicates that in response to the pandemic, 59 countries implemented remote working for non-essential publicly employed staff (ILO, 2020). Given this change in legislation, a crucial question is the extent to which workers can plausibly work from home, and which types of employees are able to change their work patterns in this way (Saltiel, 2020).

Related question: Who can work from home and how does it affect their productivity?

For developed countries, recent surveys provide economists with real-time measures of home working during the pandemic. In the United States, 50% of the employed population were working from home in April 2020 (Brynjolfsson et al, 2020). In the UK, this proportion was approximately 47% (Cameron, 2020). In Japan, where the government did not enforce a widespread lockdown, the share was around 10% (Okubo, 2020).

What does empirical evidence from developing countries tell us?

While the empirical evidence for working from home in developed countries is rapidly growing, less is known about the feasibility of remote work in middle- and lower-income countries:

- Results from comparative studies applying pre-coronavirus data indicate that developing countries have a low prevalence of jobs that are compatible with working from home in comparison with the advanced countries (Dingel and Neiman, 2020)

- Using data from the Skills Toward Employability and Productivity (STEP) survey for ten developing countries (Armenia, Bolivia, China, Colombia, Georgia, Ghana, Kenya, Laos, Macedonia and Vietnam), recent research concludes that only 13% of workers in these countries could work from home (Saltiel, 2020)

- Based on household surveys for 23 Latin American and Caribbean countries, the share of individuals who are able to work from home varies from 7% in Guatemala to 16% in the Bahamas (Delaporte and Pena, 2020)

- In comparison, in Germany this share is 56%, and in the United States, the share is 37% (Alipour et al, 2020; Dingel and Neiman, 2020)

Related question: What has coronavirus taught us about working from home?

The main reason for this variation is the difference in occupational structures. Developed countries have a higher share of higher-skilled occupations that are more likely to be performed from home than lower-skilled jobs (Watson, 2020). Customary occupations from low- and middle-income countries (such as street vendors or construction workers) cannot be fulfilled without going to the workplace.

In addition, the average income level of the country plays an important role in access to broadband internet and the likelihood of owning a personal computer, which also strongly affect the feasibility of remote working (ILO, 2020).

Despite the empirical estimations of the home working potential, real-time measures of home office activities during the pandemic are still practically non-existent for developing countries.

One notable exception to this limitation is the Brazilian Bureau of Statistics (IBGE), which conducted a nationally representative longitudinal survey with 193,662 households during the first stage of the pandemic (IBGE, 2020). The aim was to produce continuous information about the health status and labour market characteristics of the population. This research provides the opportunity to illustrate the short-term impacts of social distancing measures on home working and employment, providing insights to policy-makers not only for Brazil but also for other developing countries with similar characteristics.

In Brazil, a phone interview survey reported that 46% of the respondents believed that it would be possible for them to conduct their employment activities at home (Carta Capital, 2020). But despite this positive attitude towards working from home, real-time measures of home working during the pandemic showed a different picture. By May 2020, the evidence suggests that only 14% of the Brazilian employed population were working remotely.

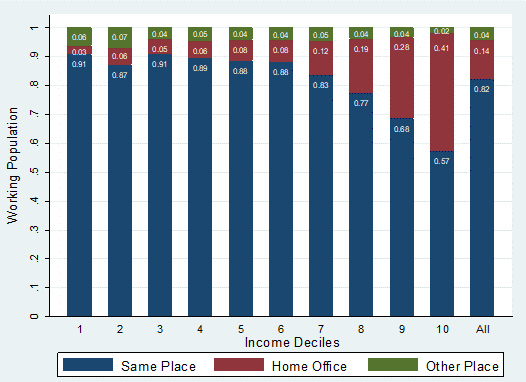

Figure 1: Workplaces during lockdown in Brazil

Notes: Income deciles use personal work income pre-lockdown. Working population refers to individuals aged 15–64 that have worked in the reference week. Percentages are weighted for population size. Workplace in May 2020.

Source: Leone, 2020.

Which groups are able to work from home?

The ability to work from home differs greatly according to socio-economic status. Quantitatively, the evidence from the survey in Brazil suggests that this share is 2.8% for the bottom 10% of the income distribution, and 40.7% for the top 10%.

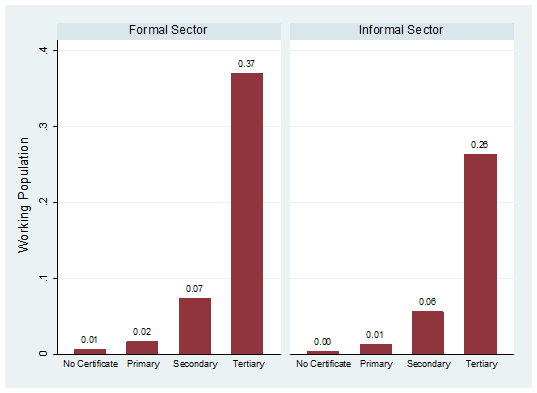

Looking at educational levels can help economists to understand this difference across income groups. In Brazil, 37% of (formal) employees with a tertiary education were able to work from home during lockdown. In contrast, only 1% of workers with no school leaving certificate were able to do so.

Figure 2: Home working by educational level in Brazil

Notes: Working population refers to individuals aged 15–64 that have worked in the reference week. Percentages are weighted for population size. Home working in May 2020.

Source: PNAD COVID19; author's own estimates.

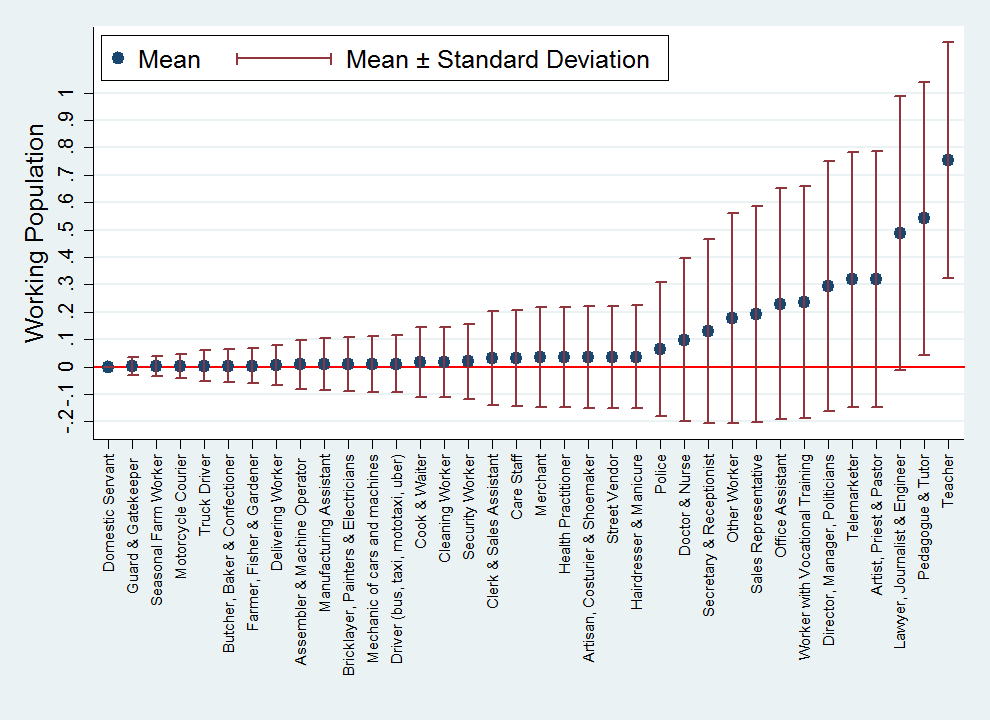

Employees with occupations requiring higher education qualifications were more often found to be working from home during the pandemic. According to the data, 75.4% of teachers and 48.6% of lawyers, journalists and engineers were working from home, while this proportion was much less for domestic servants (close to 0%), guards and gatekeepers (0.1%) and seasonal farm workers (0.1%).

Figure 3: Home working by occupation in Brazil

Notes: Working population refers to individuals aged 15–64 that have worked in the reference week. Percentages are weighted for population size. Home working in May 2020.

Source: PNAD COVID19; author's own estimates.

How might policy-makers address this issue?

Given the low prevalence of jobs that can be carried out from home in developing countries, an increasing number of analysts have warned that the vulnerable groups from the middle- and lower-income countries are more likely to suffer the negative economic impacts of coronavirus (ILO, 2020; Blofield et al, 2020).

Not being able to work from home can force workers to become economically inactive during lockdown or cause them to risk catching the virus by continuing to work during the pandemic (Bick et al, 2020; Ferreira and Schoch, 2020).

The increase in home working during the Covid-19 crisis is challenging policy-makers all over the world to ensure the same rights and benefits for home-based employees as would be available in the workplace normally (ILO, 2020). But as established, it is important for legislators to keep in mind that not all professional occupations can be carried out from home.

Because modifications in the occupational structures of developing countries are difficult to implement in the short term, policy-makers should focus on strategies to provide financial protection for the most economically disadvantaged groups during periods of lockdown. In light of this, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has recently proposed the introduction of emergency cash transfers to mitigate the worst immediate effects of lockdown measures on poor and near-poor households (UNDP, 2020).

What further evidence is needed?

The labour market impacts of the coronavirus shock still need to be explored. This is especially urgent for developing countries, where there is consistently a greater presence of work informality and a low prevalence of jobs that can be performed from home. Two main research questions should be addressed:

- For a better picture of the impacts of lockdown measures on home working and earning losses, more real-time measures of labour activities during the pandemic need to be performed worldwide.

- Since many vulnerable workers cannot stay at home during the pandemic (as they often rely on day-to-day jobs without labour protections), it is important to evaluate the impact of the income level and work informality on the Covid-19 contagion process and demand for healthcare (New York Times, 2020).

What research is in progress?

To increase our understanding of the labour market impacts of lockdown in developing countries, a number of research projects are currently underway:

- Juliana Londoño-Vélez is collecting experimental data on the impact of emergency cash assistance during the pandemic in Colombia.

- Matthew Bird is using a regression discontinuity design to investigate whether palliative cash transfers are effective to counteract the effects of stay-at-home orders in Peru.

- Marta Favara is investigating the short-term effects of the Covid-19 crisis on individual outcomes of young people in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam.

- Archanca Srivastava is analysing the impact of Covid-19 lockdown on the socio-economic condition of informal sector wage workers in India.

Where can I find out more?

- When the going gets tough: Renate Hartwig and Tabea Lakemann conduct a phone survey to investigate the effects of the pandemic on informal entrepreneurs in Uganda.

- How many jobs can be done at home?: Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman estimate the feasibility of working at home for 86 countries using occupational classifications.

- Working from home: estimating the worldwide potential: Sergio Torrejón Pérez and ILO colleagues estimate the potential share of workers across the different regions of the world who could perform their activities from home.

- Who can work from home in developing countries?: Fernando Saltiel provides comparable cross-country evidence on the feasibility of ‘telework’ for ten developing countries.

- Covid-19 in Latin America: a pandemic meets extreme inequality: Francisco Ferreira and Marta Schoch investigate the impact of the pandemic on the labour market in Latin America.

Who are experts on this question?

- Jonathan Dingel (University of Chicago)

- Sergei Soares (International Labour Organization)

- David Bell (University of Stirling)

- Merike Blofield (GIGA Hamburg)

- Francisco Ferreira (London School of Economics)