Professional sports events without spectators look set to be the norm for the foreseeable future. How is this likely to affect the economic viability of clubs, how might fans respond and what are the potential implications for grassroots participation in sport?

It is difficult to see how social distancing can be maintained while watching or taking part in sport, as for most sports they involve contact and travel. The normally rigid international sporting calendar has been wiped clean by the crisis, and it is hard to see a return to pre-crisis levels of activity any time soon. The economic and social effects of this curtailment of activity could be widespread.

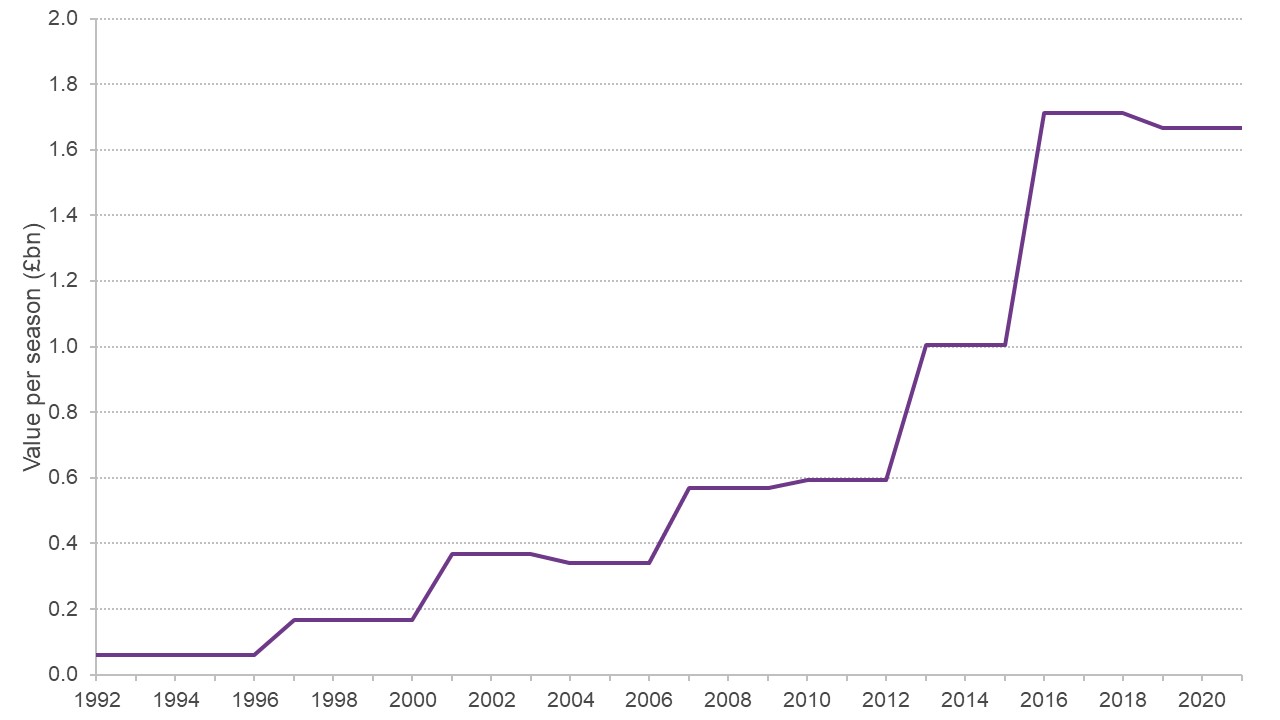

The UK sports industry has grown in recent decades, as the major leagues discovered and exploited new markets. For example, in 1992, the television rights for the English Premier League were valued at £61 million per year: in 2016, they were valued at £1.7 billion (see Figure 1).

The global crisis has led to restrictions in both supply – professional sports people unwilling to play or unable to travel – and demand – fans unwilling or unable to attend events or travel. This is in sharp contrast to the 2008/09 global financial crisis, when professional and amateur sport was largely unaffected. But this time is different, due largely to the current and expected substantial losses in revenues, as well as the dramatic disruption to the supply of sport.

Figure 1: Value of TV deals to screen English Premier League

Source: Soccerex

What does evidence from economic research tell us?

- The economics of sports are peculiar because of the unusual connections between the fans, the teams or clubs, and the institutions that manage the structure, such as a league governing body, and the ways that they interact with local communities.

- The risks of spreading an infectious disease at large-scale sporting events are high – they can be ‘super-spreaders’. This is likely to affect the number of fans who want and are able to attend events.

- Sports events without the fans present will be different. Covid-19 threatens the economic viability of the existing pyramids of sports institutions and firms.

- Sport isn’t only about watching professionals perform. The grassroots of sports rely on volunteers from among the groups most vulnerable to Covid-19.

- The crisis might also have a detrimental effect on recent steps toward addressing discrimination and inequalities in sport if it reduces the focus and resources available for tackling these issues.

How reliable is the evidence?

One of the first economists to study sports described them as ‘peculiar’ (Neale, 1964). A sports league relies on at least two firms, with essentially identical features, creating a product together. This means that there are significant costs and benefits for others from what each firm does.

To account for this, economic theory suggests that sports are best managed at a collective or league level. This can explain the emergence and long-term success of organisations like the Football League or cricket’s County Championship.

These issues are clear in the discussions taking place now between the members of various sports leagues, most notably in football, about how to conclude their seasons. Clubs demand, for example, that relegation should not happen, but promotion should.

These are not trivial decisions, with hundreds of millions of pounds at stake. In a competition such as the English Premier League, ruling out relegation is inconsistent with maintaining the interest among fans that made it successful to begin with (Borland and Macdonald, 2003).

This is referred to by economists as ‘competitive balance’ or the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis (Rottenberg, 1956) – the idea that some uncertainty about outcomes is essential to maintain spectator interest and commercial viability (Sacheti et al, 2016).

There is only limited evidence that sports fans consider the health risks of attending large-scale events. One study shows that season ticket holders at German football clubs responded to the November 2015 terrorist attack in Paris by not showing up at games in the following weeks (Frevel and Schreyer, 2019). Another study shows that fans may have stayed away from football in some European countries following news about the initial domestic Covid-19 outbreak (Reade and Singleton, 2020).

But regardless of how the fans respond now, there is evidence from economists that major sports events can significantly spread influenza, another airborne virus (Stoecker et al, 2016).

Playing professional sport behind closed doors

Sports events without spectators look set to be the norm for the foreseeable future. Many studies have investigated the causes of home advantage in sport, and there is some consensus that fans in the stadium play a role in this (Garicano et al, 2005; Buraimo et al, 2010). It has already been noticed that home advantage appears to have disappeared in the elite European football matches played without fans since Covid-19.

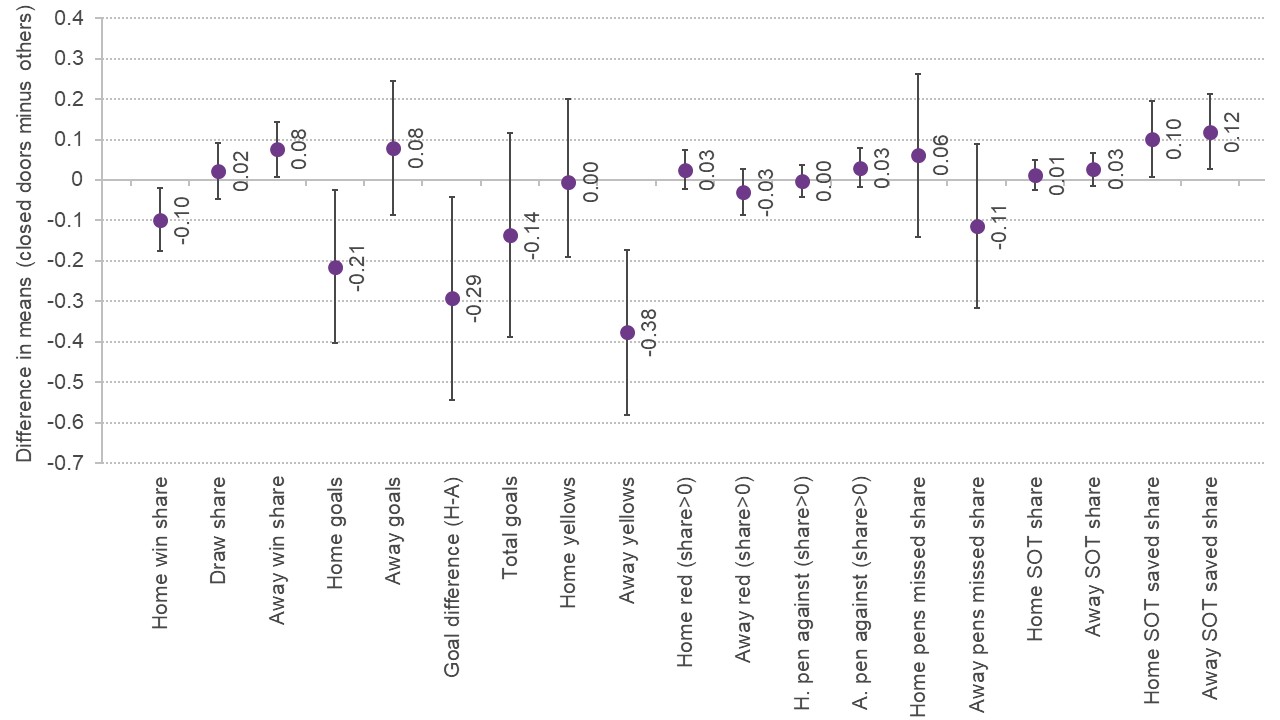

Figure 2 shows the difference in average outcomes between matches with and without fans in attendance (Reade et al, 2020). Home teams win less often and score less; away players get fewer yellow cards; and more shots on target are saved.

Figure 2: Difference in averages between matches with and without fans

Source: Reade et al, 2020

Although reduced home advantage can lead to individual sports events becoming more competitive, this depends on the differences in abilities between the competitors to begin with – weaker teams or players will have a reduced chance of springing a surprise when playing at home against a stronger opponent.

This poses a trade-off (Szymanski, 2003). The kind of fans who normally watch sports outside the stadium may have different preferences to those who attend the events (Simmons, 2006). Fans also want to see their team win and will be accustomed to home advantage. It is plausible that reduced home advantage in the long run could reduce the attractiveness of watching sports to some fans. There is also evidence that stadium attendances have a positive feedback effect on television audiences (Buraimo, 2008).

Overall, excluding spectators probably means that competition outcomes will be different, and there will be substantial revenue losses for the sports industry, over and above just the direct loss in ticket sales.

Grassroots sport

By and large, the grassroots levels of all sports rely on altruistic motives – there are no or limited financial incentives for taking part. There is clear evidence of long-term benefits from participation in sport, not just in health outcomes but also in the labour market and subjective wellbeing (Lechner, 2009). Elite sport has its role to play in this too, with evidence that the presence of role models encourages increased amateur participation (Mutter and Pawlowski, 2014).

Despite the obvious health benefits for the nation, over the decades in the UK, state funding for sports has dried up. There has been a steady move from a Spectators-Subsidies-Sponsors-Local model of sport, to a Media-Corporations-Merchandising-Markets-Globalised model across Europe, but especially in UK sport (Andreff, 2006).

Even the smallest sports clubs and ventures have bills to pay. But the model of UK sport in a Covid-19 world leaves these firms without the donations, membership fees and spectator ticket sales on which they rely. There is also evidence that volunteers, the lifeblood of the grassroots, are more likely to be in older age groups (Burgham and Downward, 2005), who are also more affected by the Covid-19 virus.

Covid-19 has disproportionately affected ethnic minority communities in the UK, while women have shouldered more of the burden of looking after dependents in the household. The image of many sports has suffered because of discrimination for a long time (Kahn, 1991; Szymanski, 2010).

Efforts to address discrimination and inequalities in sports require appropriate resources, for example, the biggest football clubs currently support the development of the Women’s Super League and make significant contributions to local community projects. Grassroots sports have suffered from physical abuse and intimidation; in the Football League, steps have been taken to promote respect (Cleland et al, 2015). As finances are squeezed in the sports industry, progress on these issues may be stifled.

What else do we need to know?

It may seem obvious that sports events could act as super-spreaders of Covid-19, and in this instance, it may be safest to go with what is obvious. Regardless, the evidence on this is currently weak. But there is some UK research now in progress about the topic.

There is limited evidence on the impact of playing sport behind closed doors on their outcomes. Preliminary evidence using historical football matches has shown that there are significant effects on a range of outcomes, including reduced home advantage. Sports played under Covid-19 may be different in ways besides the absence of the fans – for example, in terms of rule changes and the behaviour of players or officials.

More work is required to understand the implications of financial distress within the sports industry, and to advise on appropriate policy that can save clubs and leagues that have existed for generations from widespread collapse. The latest research suggests that leagues need to consolidate now to protect against the ruin of many of their members (Szymanski, 2020). Possibly the only way to save the professional sports pyramids today, without public ownership, is to leverage the future value of broadcast revenues after Covid-19.

Beyond professional sports, there are substantial unanswered questions about the long-term effects of Covid-19 on participation – and all the benefits that normally brings to public health and the economy.

Where can I find out more?

Covid-19 and football club insolvency: Stefan Szymanski sets the current crisis in the context of the financial stability of clubs in the past.

Sportseconomics.org: The Economics of Sports collects short pieces on contemporary sports economics issues, such as the influence of crowds.

The Sports Economist: analysis by US-based academics, for example, when can we expect professional sport to return?

Football returns in empty stadiums – research shows home advantage disappears: Carl Singleton, James Reade and Dominik Schreyer writing at The Conversation.

Forget the Premier League, it’s grassroots football that we need to preserve! James Reade and Daniel Parnell writing at The Football Collective.

Reading Online Sport Economics Seminars (ROSES): weekly recorded lectures since March 2020 on related topics, such as football club insolvency, how to manage the professional sports calendar and the impact of sports events on the spread of a virus.

Who are experts on this question?

- Babatunde Buraimo, University of Liverpool (research on sports demand and consumption)

- Paul Downward, Loughborough University (research on the relationships between sports, public health and social outcomes)

- David Forrest, University of Liverpool (research on betting markets, corruption and match-fixing and sports demand)

- James Reade, University of Reading (research on sports demand and betting markets)

- Robert Simmons, Lancaster University (research on sports labour markets and consumers of sports)

- Carl Singleton, University of Reading (research on sports labour markets and sporting outcomes)

- Stefan Szymanski, University of Michigan (research on the financial viability of football clubs and the social/economic importance of mega events (such as the Olympics))