The self-employed are being hit particularly hard by the Covid-19 crisis. Many have been offered a lifeline through the government’s Self-Employment Income Support Scheme – but does it go far enough?

The self-employed have experienced widespread income losses during the crisis. This has caused financial distress, exacerbated by uncertainty over future business prospects. There is also evidence of self-employed workers continuing to work despite health risks. Support offered by the government is generous to those who receive it, but there has been confusion over eligibility and a sizable group of self-employed workers are not covered.

How is the crisis affecting self-employed workers?

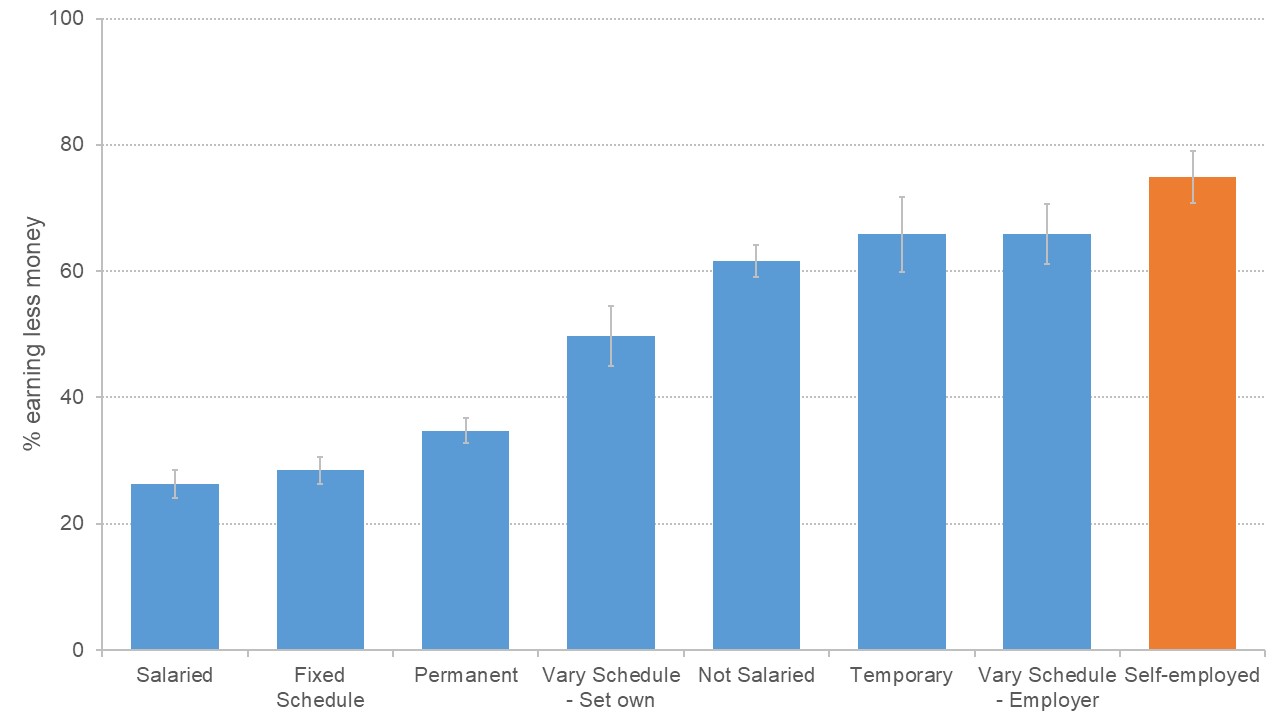

The Covid-19 crisis is having big effects on the livelihoods of self-employed workers, with one survey finding that three-quarters of self-employed workers report earning less than usual compared with one-quarter of salaried workers (Adams-Prassl et al, 2020); see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Share earning less by work arrangement

Source: Based on Figure 3 in Adams-Prassl et al (2020).

Note: Share of respondents earning less money than in a typical week by work arrangement. This excludes those who had lost their jobs at the time of the survey.

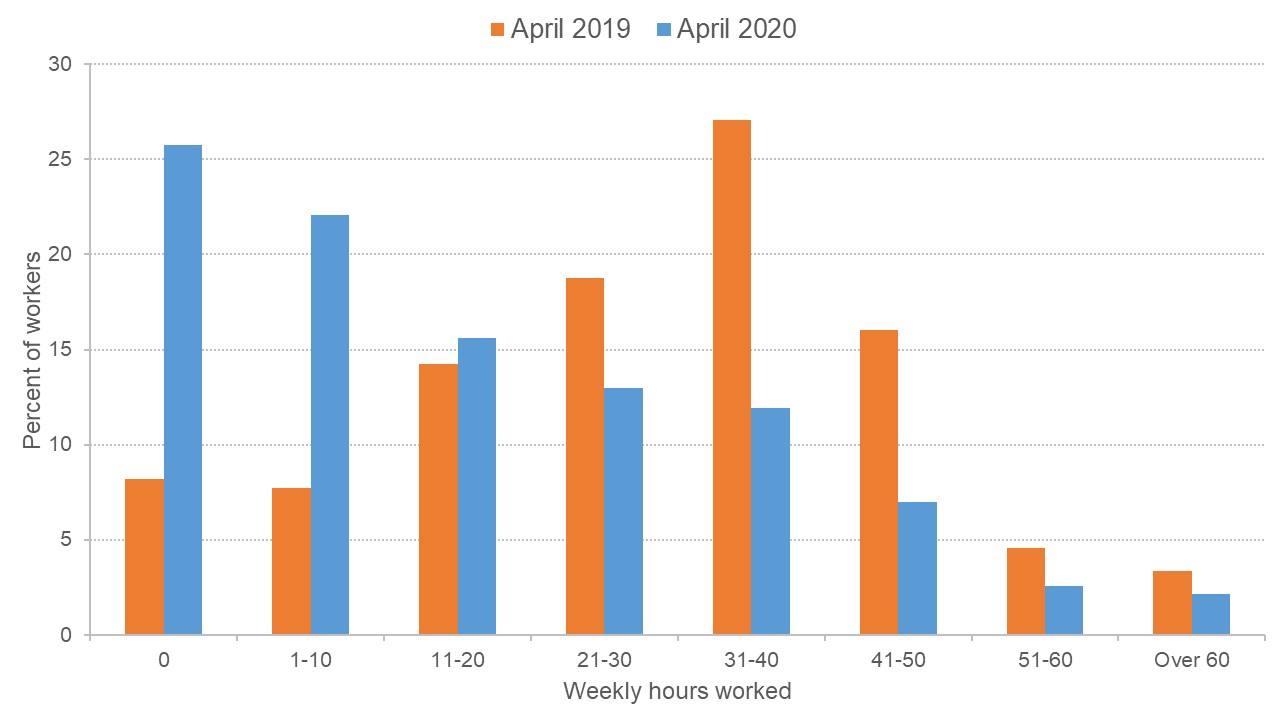

Another survey shows that the self-employed are working far fewer hours than is usual for this time of year (Blundell and Machin, 2020), as Figure 2 shows. In April, the self-employed worked an average of 11-20 hours per week, down from 31-40 hours in the previous year.

The same is true for earnings: over three-fifths of self-employed workers earned less than £1,000 this April, more than twice as many as the previous year.

Figure 2: Weekly hours in April 2019 and April 2020

Source: Blundell and Machin (2020)

Notes: Self-reported hours worked in April 2019 and April 2020 among self-employed workers.

The impact is particularly large for those on lower incomes and many are having significant financial difficulties. The same survey shows that over a third of self-employed workers have struggled to pay for essentials since the start of the crisis. The impact has also been larger for older workers and among those without employees.

The drop in hours and income has been most significant for those workers who are not able to work at home. For example, office and administrative support workers, who can perform most of their tasks from home, have fared significantly better than personal care and service workers.

The current economic situation is driven by a public health crisis. Given the lack of an employer, the inability to furlough themselves and the long wait for government support, one concern is that the self-employed may work despite health risks.

Indeed, a third of self-employed workers have felt that their health was at risk while working. This rises to nearly four out of every five (79%) ‘app workers’ – those people who are contracted through digital platforms, many of whom are delivery drivers. App workers report that the reason that they continue working despite the risks is primarily due to the financial incentives and fear of losing work in the future.

A distinctive feature of the current crisis is that women have been particularly badly affected; this was less true in the 2008/09 global financial crisis. This is in part due to the sectors in which they work and also due to greater care-giving responsibilities (Hupkau and Petrongolo, 2020).

Among the self-employed, however, there is no noticeable difference in the average impact on men and women. This is mostly because self-employed women are more likely to be able to work from home. Comparing men and women who are equally able to work from home, women are significantly more likely to report a reduction in work hours.

What support has the government provided?

The self-employed were offered a lifeline in the form of the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS). The initial round of SEISS provided a grant of 80% of average trading profits for three months. This was capped at £2,500 per month for a maximum grant of £7,500. On 29 May, an additional round of grants of up to £6,570 was announced, to be disbursed in August.

Payments are not linked to financial loss experienced during the crisis and unlike furloughed workers, the self-employed can continue to work while receiving the grant. Given this, workers who receive only a small income loss could be quite substantially better off than if the crisis had not occurred (Adam et al, 2020). This highlights the challenge of targeting support towards those who most need it among self-employed workers.

Applications for the first round of SEISS grants opened on 13 May. There were two million successful claims for this support in the first five days of opening, representing nearly half of self-employed workers.

Take-up among those eligible for support has been high, but analysis from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) shows that around two million people with some self-employment income will not be covered by the SEISS. These include people who received less than half their income from self-employment, many of whom will be eligible for the furlough scheme. It also includes the small number of self-employed workers who had annual profits of over £50,000 in previous years.

The newly self-employed – those who entered self-employment since April 2019 – are also excluded. The IFS estimates that there are 650,000 of these workers. This group is neither particularly high-income nor are they covered by other schemes. In recognition of this, they have received a small amount of additional support in Scotland through the Newly Self-Employed Hardship Fund, but remain without support across most of the UK.

There is evidence of uncertainty of eligibility among the self-employed. Soon after the first round of SEISS opened, 41% of those who had not claimed were unsure whether they were eligible or not (Blundell and Machin, 2020).

Given the wait until late May for the first round of SEISS grants, it is unsurprising that many of the self-employed have turned to Universal Credit (UC) to support themselves. While the generosity of UC has been increased for all workers, this is particularly true for the self-employed. Most significant is the removal of the minimum income floor, which previously had reduced the in-work support available to self-employed workers relative to others.

Related question: Will government measures protect the most vulnerable in society?

A recent report finds that over one-in-four new UC claimants during the crisis were self-employed (Brewer and Handscomb, 2020). The removal of the seven-day waiting period for entitlement to Employment and Support Allowance was specifically targeted to help self-employed workers, in place of Statutory Sick Pay. This expansion of alternative modes of support will be welcomed by those falling through the cracks in SEISS eligibility.

Where can I find out more?

Self-employment in the Covid-19 crisis: Jack Blundell and Stephen Machin at the Centre for Economic Performance discuss evidence from their targeted survey of self-employed workers.

The effects of the coronavirus crisis on workers: flash findings from the Resolution Foundation’s coronavirus survey: Laura Gardiner and Hannah Slaughter of the Resolution Foundation present evidence on the unequal impact of the Covid-19 crisis on different categories of workers, using data from their new ‘Coronavirus Survey’.

Income protection for the self-employed and employees during the coronavirus crisis: Stuart Adam and colleagues from the Institute for Fiscal Studies analyse the Job Retention Scheme and the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme.

Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: new survey evidence for the UK: Abigail Adams-Prassl and co-authors show how the unemployment shock in the UK affects those of different ages, different earnings levels and different employment contract types.

Who are UK experts on this question?

- Helen Miller and Stuart Adam have written extensively on tax reform for self-employment as well as on the details of the SEISS support.

- Giulia Giupponi has written on flexible labour market arrangements and policy.

- Jack Blundell has written on the impact of the crisis on UK self-employment, as well as about the characteristics of UK self-employed workers before the crisis.

- Abi Adams-Prassl has written on the gig economy and the effect of technology on labour markets, particularly surrounding alternative work arrangements.

- Stephen Machin has written a number of papers on solo self-employment and alternative work arrangements.