Young people’s mental health has suffered more than that of older age groups during the pandemic. There is a particular need for support for vulnerable children, teenagers and young adults to prevent existing inequalities in education and employment from widening.

Over the course of the pandemic, young people’s education, jobs and social lives have been interrupted. But we are still learning about how the events of the past 18 months have affected their mental health. Evidence suggests that younger age groups (16-24 year olds) have fared worse, on average, than older age groups in terms of their mental health.

Increases in mental ill-health have not been uniform. Those who are more likely to face poor circumstances at home or whose pre-pandemic mental distress was already elevated appear to have seen greater declines in wellbeing.

In the long-term, mental ill-health can lead to lower educational attainment and diminished employment opportunities. The declines in mental health seen during the pandemic among those who already face disadvantage therefore raises concerns that existing inequality gaps in education and employment will grow without intervention.

How is the crisis affecting young people’s mental health?

Multiple studies have documented an increase in self-reported symptoms of poor mental health or a rise in helpline calls during lockdowns (Armbruster et al, 2020; Brülhard and Lalive, 2020; Office for National Statistics, 2020; Yamamura and Tsutsui, 2020). Self-reported wellbeing and anxiety were particularly affected, worsening during these periods.

A survey of young people aged 13 to 25 carried out during the January 2021 lockdown found that 75% of respondents reported later lockdowns had become increasingly difficult to cope with. In addition, 67% believed that the pandemic would have a long-term negative effect on their mental health. The most frequently cited factors for negative effects on mental health were loneliness and concerns about school, suggesting issues related to social contact and additional stressors as significant factors in creating mental distress during these times.

A study using individual-level longitudinal UK data to assess the interaction between the pandemic and mental health trends across different age groups finds that young people have been particularly affected by the crisis (Banks and Xu, 2020). The authors compare the predicted mental health trends based on pre-pandemic data with actual pandemic trends. They show that the deterioration in mental health since the onset of Covid-19 has been especially strong for those aged 16-24. This group also experienced a much stronger rise in the number of who report encountering problems or severe problems.

Additional studies have collected data across wider age ranges, yet the picture is not entirely clear, and more work is necessary. Higher reports of loneliness during lockdowns have been found among older children relative to younger children (Mansfield et al, 2020).

Symptoms have not been strictly limited to nor always present among older children. Rather, the symptoms experienced by an individual appear to differ across dimensions, with some evidence that younger children have experienced greater behavioural problems (Ford et al, 2021). In other cases, teenagers have reported improved or unchanged symptoms over lockdowns (Vizard et al, 2020; Windall et al, 2020).

But evidence on these trends among younger groups of children and adolescents tends to be highly descriptive. They note simple changes in averages that do not isolate differences between what the trend may have been without the pandemic or entirely explain the changes, leaving scope for further research.

Improvements in mental distress among some young people and deterioration among others is in line with earlier predictions. In the original version of this article, inequalities in mental health outcomes were a salient concern. Other work has also shown how some young people have been affected more than others. One study finds that those with heightened levels of pre-pandemic mental health distress have suffered considerably more relative to those with lower pre-pandemic levels (Banks and Xu, 2020).

Evidence also suggests that symptoms of mental distress have primarily worsened for young people living in lower income families (Waite et al, 2020). These patterns suggest that the effects of the pandemic on mental health are likely to have exacerbated pre-existing inequalities among young people. This may be due to fewer family resources in disadvantaged homes, leading to more stress and environments that increase vulnerability to mental distress. But more research is needed to understand exactly why this is the case.

What do the data reveal about young people’s mental health during Covid-19?

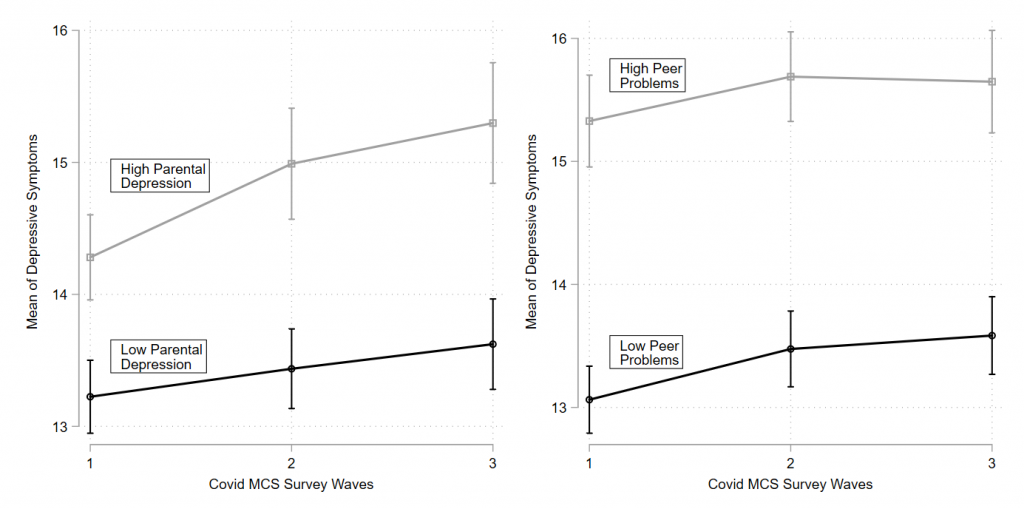

To provide more context on trends in mental health among young people, Figure 1 uses information from members Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) who participated in the three repeated sweeps since the beginning of the pandemic. The MCS is following the lives of around 19,000 young people born in the UK in 2000-02.

Figure 1: Trends in depressive symptoms for MCS members

Source: Author’s calculations, Millennium Cohort Study (MCS)

Note: author's own calculation from regression of the Kessler 6-item scale on indicators for the MCS Covid wave where interactions are added for the relevant splits. Pre-pandemic, MCS sweep 7 Kessler scores are controlled for in each regression. Parental depression is split around the media of the parental Kessler score and peer problems around he median of pre-pandemic peer problems. All regressions account for sampling unit, design weights, and strata, as discussed in the UCL Cohorts Covid-19 Survey User Guide.

The first Covid-19 survey wave took place in May 2020, with wave two in the late summer and early autumn of 2020, and wave three in February and March of 2021. These have provided a wide coverage over the course of the pandemic so far. Survey respondents were born in 2000-02 and by the last pre-pandemic survey in 2018 were on average 17 years old. While this group is now at university/working age and do not shed light on trends for younger children, they are nevertheless a relevant population of young people.

The results shown in Figure 1 are descriptive but highlight some insightful patterns. The left panel demonstrates that increases in depressive symptoms have on average been focused on those who experience a worse home environment (in terms of facing higher parental depression). While both groups saw some rise in symptoms, for the young people whose parents were more depressed, their symptoms have trended upward more strongly over the course of the pandemic.

In the right panel, the picture is different. There is a level gap across those who reported more or less peer problems at the last pre-pandemic survey. This means that on average those reporting higher pre-pandemic peer problems also report high levels of depressive symptoms. But there is no suggestion of a difference in trends and no significant rise in symptoms over the pandemic for either of these two groups.

These patterns further suggest that changes in depressive symptoms among young people have not been uniform. Rather, they may be partly driven by whether and how the pandemic has affected other areas of their lives – such as their home environment – which may affect their wellbeing. As a result, young people may also be affected differently by the return to school or university.

What are the potential longer-term effects?

The impact of the pandemic on young people’s mental health appears to be more significant for those exposed to more deprived or generally harmful home conditions. There is also evidence that workers who are low earners have faced the worst of the employment and income shocks since the onset of the pandemic (Brewer and Handscomb,2021). This means that families that are likely to be dealing with the most significant loss of resources will also be the ones where the mental health of young people is already at greater risk.

In addition, research shows that young people who have suffered from depressive episodes are much more likely to experience future episodes (Momen et al, 2020; Thapar et al, 2012).

In the long term, without intervention to alleviate both economic shocks on vulnerable populations and elevated mental health problems among their young people, these individuals will be at greater risk of poor mental health in the future.

Additionally, in the short-term, recent evidence shows that pupils in England have experienced substantial learning loss relative to pre-pandemic periods. This loss appears across year groups and regions and is strongest for those in more disadvantaged schools (Department for Education, 2021). Evidence from the Netherlands also indicates that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds have suffered greater learning losses (Engzell et al, 2021).

This places those populations of young people who appear at greater risk of mental ill-health among those suffering the most from lost learning over the pandemic. This is worrying as factors such as poor mental health that reinforce educational loss will be likely to cause further harm to their educational progress, creating long-term educational inequality.

The long-term risk for young people within disadvantaged populations also raises economic risk. The cost of mental health issues has been estimated at close to 2.5% of GDP in the United States, while in Europe it has been estimated to be near 3.5% (OECD, 2015). These costs may run through lost productivity, such as absenteeism due to mental health problems.

Beyond direct costs, however, young people themselves will face lower educational attainment and poor labour market outcomes as consequences of mental ill-health. This may also affect the economy through reductions in human capital (Biasi et al, 2019; Cornaglia et al, 2015; Currie and Stabile, 2006; Fletcher, 2010).

While there is still more work needed to understand the mechanisms around adolescents’ mental health over the pandemic, there are clear incentives to act. Poor mental health creates costs both for individuals and through long-term spillovers to the economy. The long-term effects can increase inequality that has already grown in the short run over the course of the crisis.

Where can I find out more?

- OxWell School Survey: Karen Mansfield, Christoph Jindra and Mina Fazel at the University of Oxford have been analysing an extensive dataset collected on children in England during 2020 to assess the impact of school lockdowns on children’s wellbeing.

- Young People’s Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Emily Widnall, Judi Kidger, Lizzy Winstone, Becky Mars and Claire Haworth with the University of Bristol have run a project over 2020 that surveyed and assessed a sample of Year 9 students in southwest of England to examine their mental wellbeing in response to lockdowns and return to school.

- Covid-19 Social Study: This study on mental wellbeing is run by the University College London and led by Daisy Fancourt and Andrew Steptoe.

Who are the experts on this question?

- James Banks, Professor of Economics at the University of Manchester

- Xiaowei Xu, Senior Research Economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies

- Judi Kidger, Senior lecturer in Public Health at the University of Bristol

- Richard Layard, Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics