The prices of Bitcoin, Ethereum and other cryptocurrencies have been plummeting. While the trigger was changing economic conditions, the root cause of the crash lies in the nature of crypto investments: they lack independent value and require a continuous stream of new investors to sustain prices.

Cryptocurrencies are digital assets that purport to be a form of money. Since the beginning of 2017, increasing interest in the concept has caused their prices to soar, making many early adopters rich. As a result, they are now generally promoted as investment assets rather than money assets. But the prices of popular cryptocurrencies have recently collapsed (see Figures 1-3). Why?

Figure 1: Bitcoin price (dollars), June 2019-June 2022

Figure 2: Ethereum price (dollars), June 2019-June 2022

Figure 3: XRP price (dollars), June 2019-June 2022

Source: Yahoo! Finance

To appreciate what is happening, we need to understand the nature of cryptocurrencies as investments. In finance, we typically evaluate investments by assessing their associated future cash flows. For example, if we want to understand how much a share in a company is worth, we try to estimate how much money the business might make in the future.

A small number of investment assets, such as gold, are useful to investors despite producing no cash flows. This is usually because extensive historical data indicate that their price tends to rise when other assets are losing value. Including them in a portfolio of investments can therefore reduce the investor’s level of risk.

Depending on investors’ risk preferences, this may offset the reduced expected return arising from the absence of cash flows. These assets are also commodities: they would still be useful to their holder even if no one was willing to buy them.

When evaluated as an investment, cryptocurrencies are unique – and not in a good way. In the vast majority of cases, they do not entitle the holder to any cash flows; their price does not appear to rise when other investments are falling; and they have no value beyond the willingness of another person to pay for them.

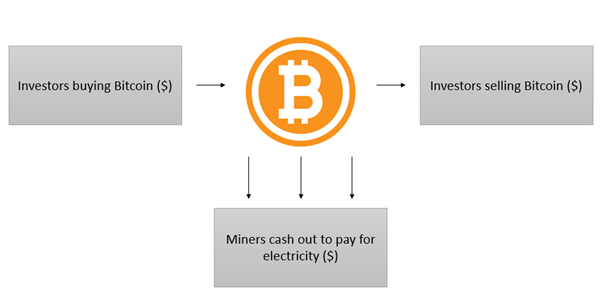

In addition, the most popular cryptocurrencies incur substantial energy costs. Bitcoin’s ‘proof-of-work’ verification system gives investors incentives to use computing power repeatedly to guess a very large number, with the closest guess receiving newly minted Bitcoin. This burns through an estimated $6.5 billion of electricity per year. Since these electricity costs cannot be paid in Bitcoin, the system is negative-sum: more money will be lost by the losers than is gained by the winners.

Figure 4: The negative-sum cash flows of Bitcoin

This means that the cryptocurrency ecosystem requires a continuous inflow of new investment just to keep prices at the same level. Positive returns can only come from future investors who are willing to pay a higher price.

The only other class of ‘investment’ for which this is always true is Ponzi or pyramid schemes, two common forms of fraud in which money from late investors is used to pay unsustainably high returns to early investors. Similar to Ponzi schemes, crypto investors often advertise the coins they hold aggressively in an effort to attract newcomers (a practice commonly known as ‘shilling’).

Another way to increase the flow of cash into the system is via the use of debt. For example, rather than buy $1,000 worth of Bitcoin, an investor might use that $1,000 as collateral for a loan of $10,000 and buy $10,000 worth of Bitcoin (this is generally known as margin trading).

Since this generates ten times more demand, margin trading will cause prices to rise more quickly in a bull market – a period when an asset’s price rises continuously. But the lender typically retains the ability to force the borrower to sell if their investments fall below a certain level – the dreaded ‘margin call’. These forced sales mean that prices will also fall more rapidly on the way down.

Another significant form of debt in the crypto ecosystem involves stablecoins. These are cryptocurrencies that are ‘pegged’ to the value of a traditional currency, usually the dollar. They are often issued without being fully backed by underlying dollars, with the excess stablecoins invested in crypto assets.

Effectively, this means investing depositor money multiple times, in much the same way as a fractional reserve bank (where only a portion of deposits are backed by cash and therefore available for withdrawal). Since it incurs liabilities, it constitutes another form of debt.

At the time of writing, the largest stablecoin, Tether, had 67.9 billion Tethers outstanding. The quantity of dollar equivalents backing these assets is unknown but has previously been at levels as low as 6%. In other words, the Tether Corporation had at that time issued over 16 Tethers for every dollar it owed to depositors. This represents another significant source of debt, and the potential failure of the Tether peg is widely considered as a systemic risk to the crypto sphere.

Partially backed stablecoins can simply be used to buy other cryptocurrencies, increasing their price even when no new dollars are entering the system. More commonly, they are used to collateralise margin trading in the manner outlined above, layering one level of indebtedness on another.

Importantly, the fundamental negative-sum nature of cryptocurrencies is not changed by all of this debt. More leverage can postpone the crash, but it cannot prevent it, and it is likely to make it more sudden and painful. Research shows that debt-fuelled bubbles tend to be much more economically destructive than other bubbles (Quinn and Turner, 2020).

The current drop in the price of cryptocurrencies is simply the result of this debt-fuelled, negative-sum system unwinding. As a result of the increasing cost of living, rising interest rates and post-pandemic return to normality, the flow of new money entering the system has dried up.

Falling prices are leading to margin trader liquidations, financial difficulties at major crypto firms and stablecoin collapses. These events impose losses on other participants in the crypto economy, who may themselves default on debt, creating a vicious downward spiral. This momentum can only be stopped by finding a way to generate a new influx of dollars or to prop up prices temporarily with more debt.

The trigger for the crash was a change in the economic environment, but its root cause is that cryptocurrencies have always been fundamentally unsound long-term investments. History tells us that negative-sum assets with no use value cannot hold their value indefinitely. As is often the case during a bubble, the promise of ‘getting rich quick’ appears to have blinded many participants to the economic reality.

The big question for policy-makers now is whether this poses a threat to financial stability. Fortunately, the extent of institutional investment in crypto has been heavily exaggerated, and systemically important banks are unlikely to have much direct exposure to the crash.

The main risk to stability comes from the possibility that the banks are indirectly exposed in a way that they themselves do not fully understand. This was the case during 2021’s Archegos scandal, when the collapse of an investment company triggered banks and other investors to lose billions of dollars.

The bad news is that money lost in crypto investments is almost certainly gone forever. Investments with regulated UK financial services firms are often partially covered by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, and deposits at banks are covered by deposit insurance. But since crypto is largely unregulated, money held at crypto exchanges or investment platforms is not covered. Although the crypto crash is unlikely to cause the next great recession, the losses to individual investors could be severe.

Where can I find out more?

- The latecomer’s guide to crypto crashing – Amy Castor and David Gerard – an outline of the crypto firms and stablecoins that have collapsed so far, and those that appear to be in distress.

- Are Bitcoin and other digital currencies the future of money? An assessment of the strengths and limitations of Bitcoin as a currency.

- Why has the price of Bitcoin rise/fallen in the past day/week/month? An assessment of the factors that drive short-term fluctuations in the price of Bitcoin.

- Web3 is going great – a continually updated timeline of failures, hacks and lawsuits affecting cryptocurrencies and other associated projects.

Who are experts on this question?

- Frances Coppola

- John M. Griffin

- John Paul Koning

- David Gerard

- Andrew Urquhart

- Eric Budish