Paris hosted the 2024 Summer Olympic Games – the 30th of the modern era. Memories will be dominated by great sporting moments, including athletes winning their countries’ first ever medals. But the mega-event also highlighted issues around representation, equality, cost control and home advantage.

Paris has been the host for the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Over the course of the summer, the city – and other venues across France – have welcomed 10,500 Olympians (competing in 32 sports) and over 4,000 Paralympians (competing in 22 sports).

Here, we summarise some of the numbers and stories related to recent Olympic Games.

Growing representation

In the Paris games, 206 territories were represented, alongside the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Refugee Olympic Team. Comparably, the 1900 Olympics – also hosted by Paris – featured athletes from only 24 nations.

The increase in participating countries has been consistent aside from a noticeable break in 1980 when the Moscow games saw the largest Olympic boycott in history (see Figure 1).

The American-led boycott of that edition was instigated by political tensions with the Soviet Union over its occupation of Afghanistan. Approximately 60 countries joined the United States in boycotting the games, resulting in only 81 countries sending athletes.

Figure 1: Number of countries at the Summer Olympics

Source: Statista, 2024

The size of athlete delegations at the 2024 games was highlighted during the opening ceremony on the river Seine, with some countries needing large double-decker boats, while others waved their flags from small Murano boats. So, which countries were the most and least represented?

China (with 388 athletes) and the United States (with 594) had among the largest delegations, while countries like Australia (460 athletes), France (572), New Zealand (212) and Slovenia (74) all had high numbers of athletes at the games relative to their population size (see Figure 2).

At the other end of the scale are countries with large populations that had far fewer athletes competing. These included Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan with only five, two and seven athletes respectively. Somalia – a country of over 18 million people – had just one athlete in Paris, while the Netherlands – with a similarly sized population – had a team of 276.

Figure 2: Olympic representation, athletes versus population

Source: IOC, World Bank, 2023 population estimates

This trend is likely to be driven by resource disparity. Pakistan – a country of over 240 million people – is thought to have the lowest level of sport funding in South Asia, with an overall sports budget allocation of $5.7 million in 2020/21. This is around 23 times lower than the £100 million invested by UK Sport each year in high-performance sport.

In Paris, Pakistan won their first individual Olympic gold in the country’s 77-year history, courtesy of Arshad Nadeem’s Olympic record javelin throw. Comparably, Team GB won 25 gold medals.

Gender balance

Organisers set out for the 2024 games to be the most gender-balanced in history. The target of equal representation between men and women athletes was likely just missed, with the proportion of women competing expected to be closer to 49% – a marginal improvement on Tokyo 2020. The previous Paris games, held in 1924, saw just 135 women compete out of over 3,000 athletes.

In recent games there has been progress towards gender-parity in the event schedule. This continued in Paris, with women competing in 172 events and men competing in 177 events (see Figure 3). Further, 28 of the 32 sports were ‘fully gender equal’.

The 1900 games were the first to allow women to compete, though only in croquet, equestrian events, golf, sailing and tennis. With the introduction of women’s boxing, London 2012 was the first time that women competed in all sports on the programme.

Many teams sent more women athletes to Paris 2024 than men. Team GB and Team USA were among these, while Guam had the highest representation of women at 87.5% (seven of its eight athletes). Six nations (Belize, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Liechtenstein, Nauru and Somalia) had no women competing in their teams.

Figure 3: Number of Olympic events by gender

Source: Statista, 2024

Efforts to ensure gender parity have been further supported by initiatives like the rule introduced at Tokyo 2020 that allowed one male and one female athlete to carry their nation’s flag jointly during the opening ceremony. According to the IOC, 91% of countries had a female flag bearer, enhancing the visibility of women competitors.

New sports

Paris 2024 saw one new sport, with the introduction of breaking (break-dancing). When introduced at the youth Olympics, breaking was incredibly popular, with one million viewers tuning in. A further three sports – skateboarding, sport climbing, and surfing – returned after debuting at Tokyo 2020. Paris 2024 organisers targeted sports that are ‘closely associated with young people and reward creativity and athletic performance’.

A 2021 YouGov survey examined the popularity of Olympic sports at the Tokyo games by region and gender. Fans in Germany and the UK were mostly likely to follow athletics, while those in the United States favoured artistic gymnastics. Swimming featured among the top five sports in China, Germany, the UK and the United States.

Swimming was the most popular event overall at the Tokyo games, followed by athletics. Diving and gymnastics were more popular with women fans, while team sports such as basketball and football were more popular among men (see Figure 4).

Boxing was approximately twice as likely to be followed by male fans – the fact that women’s boxing was only introduced in the 2012 games may have an influence here. Similarly, Tokyo 2020 was the first time that sport climbing and surfing featured on the programme, which might explain why the sports were relatively less popular with both men and women.

Figure 4: Popularity of Olympic sports by gender

Source: YouGov, 2021

Medal distribution

As international participation in the Olympics has grown, the distribution of medals has become more equitable. Paris 2024 marks a slight reversal in this trend, with the top ten countries winning 63% of available medals (see Figure 5).

At Paris 1900, the city’s first Olympics, the top ten countries in the medal table won over 98% of available medals. Towards the end of the 20th century, the top ten countries routinely won over 70% of the medals available.

At Tokyo 2020, this fell to only 55%, with countries ranked 40th and below in the table winning a record 13% of all medals. This was a positive development, indicating a more level playing field in global competition.

In Paris, four countries, as well as the Refugee Olympic Team, won their first-ever medals. One high profile example was Saint Lucia’s Julien Alfred who won gold in the women’s 100m sprint.

Figure 5: Olympic medal distribution by table ranking

Source: Olympedia, IOC

In recent Olympics, China and the United States, and Great Britain and Northern Ireland have tended to feature at the top of the official medal table, as ranked by gold medals.

When taking a different approach to success, other big winners emerge. Looking at victory ratios – which consider a country’s ratio of events entered to medals won – reveals that Kenya, North Korea and Saint Lucia outperform the usual Olympic giants (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Paris 2024 victory ratios: share of events entered where medals were won

Source: Olympedia, IOC

Saint Lucia, with a population of just 180,000, won their first Olympic medal, courtesy of Julien Alfred, who also won silver in the 200m sprint. This gave her country a 50% medal success ratio for the four events entered.

Team France won medals in a quarter of the events entered, rising from 10% in Tokyo and placing them 15th in the victory ratio table. Larger nations such as Canada and Germany experienced defeat in nearly 85% of their events. Through this lens, some of the biggest winners might also be considered the biggest losers.

Prize money

The Olympics can be highly lucrative for some athletes, but not for all. The IOC maintains an official policy of amateur competition, so it does not reward medallists or pay athletes to compete.

With no universal compensation regime, athletes’ earnings depend on their sport, their performance, corporate sponsorship and, most importantly, their country.

While the Olympics as a whole is governed by the IOC, each sport is governed by its own international federation, which has autonomy over their IOC-allocated funds. This year, two broke with the IOC’s amateur athletics tradition.

World Athletics – the governing body for track and field – elected to reward gold medallists, paying $50,000 (around £39,400). The International Boxing Association announced that it would reward medallists and their coaches: for gold, $100,000 for the boxer and $25,000 for the coach, $50,000 and $25,000 respectively for silver, and $12,500 apiece for bronze.

Several National Olympic Committees (NOCs) also have medal compensation policies (see Figure 7). At the Paris games, Hong Kong had the most generous scheme, paying its gold medallists HK$6,000,000 (around £590,000). Singapore and Taiwan are among the other nations that offer financial incentives to their athletes.

Figure 7: Medal compensation

Source: Authors’ calculations

Not every NOC compensates their medallists this generously or at all (see Figure 8). Indeed, of the ten largest teams, only Italy and Spain compensate gold medallists more than $100,000 (around £76,700).

Figure 8: Medal compensation among largest participants

Source: Authors’ calculations

For most athletes – those who do not win medals or who compete in less popular events – earning money from the Olympics is less likely or certainly less lucrative. For example, UK athletes with strong medal prospects receive money from Athlete Performance Awards (APAs), which are funded by the National Lottery.

APA awards, which reach a maximum of £28,000, typically with no tax incurred, are designed to allow athletes to train full-time. Funding pots can vary by sport, with athletes and sports deemed unlikely to win medals often hit with large budget cuts.

For example, following the Rio de Janeiro games in 2016, British fencing lost its funding of £4.2 million, leaving athletes to self-fund the normal competition circuit.

Funding towards full-time athlete status is not available in many countries, including some of the richest. No official count is available, but it is widely believed that the majority of Team USA athletes must work part-time or even full-time jobs in addition to their Olympic training schedule.

Russia’s ban

Due to the Russian Olympic team’s historic doping violations and the war in Ukraine breaking the Olympic truce, Russian and Belarusian athletes were largely barred from the Paris games. Only 15 Russians and 17 Belarusians competed as ‘individual neutral athletes’ under strict neutrality rules.

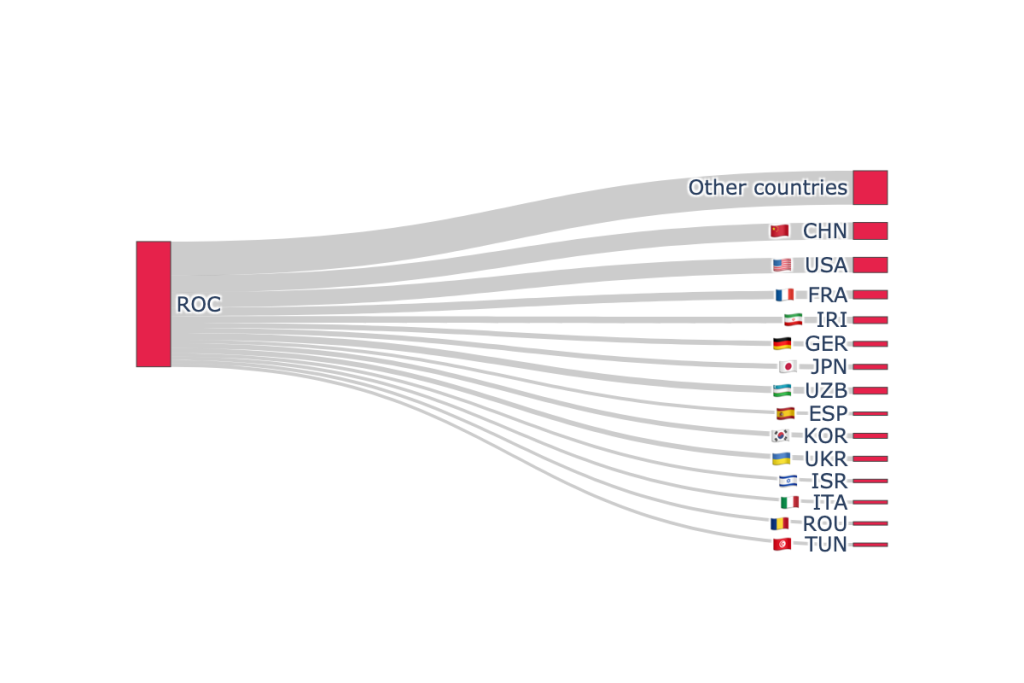

The absence of Russia in Paris meant that the medals that might have been won by Russian athletes were redistributed across many countries. At the Tokyo games, the Russian Olympic Committee (ROC) won 71 medals, including 20 golds, finishing fifth in the medal table.

Medals won by Russia in Tokyo were distributed across 32 nations in the Paris games. No single country significantly benefited but China and the United States claimed the most (ten and nine respectively), while others shared the rest (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Distribution of total medals won by Russian Olympic Committee in 2020 Olympics in 2024 Olympics

Source: Wikipedia, authors’ calculations

Home advantage

Ahead of the games, France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, set the goal for his country of finishing in the top five of the medal ranking. The French team achieved this – winning 16 golds to place fifth. In total, France picked up 64 medals, almost double what they won in Tokyo 2020 (see Figure 10).

This was also France’s highest medal haul since the second Olympics in 1900. Some of the notable medal gains came in cycling (nine medals in 2024 compared with two in 2020) and swimming (seven medals in 2024 versus just one in 2020).

Figure 10: France’s daily cumulative medal count in the Summer Olympic Games

Source: IOC, Olympedia

France’s success was perhaps not a surprise given that host nations tend to perform better, due to several factors, including increased investment being funnelled into national sport programmes. With 572 athletes, France also entered the competition with its largest delegation since 1900.

Cost control

As the Olympics have grown, so have the costs of hosting (see Figure 11). Paris 2024 is projected to have cost approximately $8.7 billion, with $1.5 billion dedicated to cleaning up the river Seine for swimming events.

This expensive effort was still unable to prevent the high levels of water contamination from affecting certain events. Some open-water events, such as the men’s triathlon and the women’s marathon swimming, had to be postponed several days due to high bacteria levels in the water after heavy rainfall.

The large sums associated with hosting have led to debate over the costs and benefits of doing so. Tokyo 2020 continued a decades-long trend of overrunning costs, exacerbated by the unprecedented delay due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The cost of the most expensive Olympics – the Sochi Winter Games in 2014 – were predominantly driven by infrastructure costs, security concerns and fund-draining corruption.

Figure 11: Olympic costs of hosting, summer and winter

Source: Budzier and Flyvjerg, 2024

The IOC requires host cities for the summer games to have a minimum of 40,000 available hotel rooms. To meet this, over 15,000 new hotel rooms, as well as upgrades to transport links, had to be built in Rio de Janeiro in time for the 2016 games.

Given that Paris already hosts a significant number of tourists and has over 1,600 hotels, these particular cost pressures were alleviated. Indeed, in July, Parisian hotels were struggling to fill rooms due to lower demand during the Olympic season than expected.

Although initial hosting costs can be burdensome, many countries justify the expense by balancing the long-term benefits. Investment in infrastructure can have positive spillover effects for the economy, providing work and opportunity for locals.

The legacy of London 2012, for example, focused on regeneration of the east of the city. The venues have created jobs for local people by staging high-profile events and attracting more than six million visitors a year. Following the 2012 games, the UK government set a four-year plan to secure at least £11 billion of economic trade and investment benefits from the games. This target was met within 14 months.

Another justification for investing in the Olympics is the belief that hosting and winning medals will boost grassroots participation in sport. Yet evidence, including from the London games, does not back this up.

Conclusion

Over 19 days of competition and 329 events, the Paris Olympics attracted billions of viewers across the globe. The games produced 350,000 hours of television broadcasting the different sports and medal ceremonies.

As with Olympics of the past, we are likely to remember great sporting moments, including athletes winning their countries’ first ever medals. But the games also raise questions about investment in hosting, and in sport more generally, whether at the elite or grassroots level.

Where can I find out more?

- Who wins the Olympic Games: Economic resources and medal totals: Article in the Review of Economics and Statistics by Andrew Bernard and Meghan Busse.

- Explaining international sporting success: An international comparison of elite sport systems and policies in six countries: Article in Sport Management Review.

- An analysis of country medal shares in individual sports at the Olympics: Article in European Sport Management Quarterly.

- The Olympic effect: Article by Andrew Rose and Mark Spiegel in the Economic Journal.

- The more medals Canadian athletes win, the fewer Canadians participate in organized sport: Article in The Conversation by Peter Donnelly and Bruce Kidd.

- Grassroots participation in sport and physical activity: UK House of Commons report.

Who are experts on this question?

- Veerle De Bosscher, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

- Victor Matheson, Holy Cross College

- Johan Rewilak, University of South Carolina

- Dominik Schreyer, WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management

- Peter Donnelly, University of Toronto

- Bruce Kidd, University of Toronto

- Svein Erik Nordhagen, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Lillehammer, Norway

- Gregory Papanikos, Athens Institute