Only one in ten of the UK’s top businesses have a woman as chief executive. Several factors explain this imbalance: from discrimination and a lack of networks to low confidence and the ‘motherhood penalty’. Investment in childcare and more diverse boards could help to close the corporate gender gap.

Women account for 49% of over 16-year-olds in employment in the UK. Yet of the one hundred chief executive officers (CEOs) currently heading the country’s biggest public companies by market capitalisation (the FTSE 100), only ten are women.

There is a lack of diversity among UK CEOs in terms of race, class and educational background (Equality Group, 2023). But the lack of diversity is greatest for women.

Figure 1: Women CEOs of large companies in advanced countries (%)

Source: Data collected by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) from January 2017 and previously by the European Commission.

Note: Based on the percentage of women CEOs at the time of the annually published Fortune 500 list.

The current share is an improvement from 2020 when there were more CEOs named Peter than women.

Progress has also occurred on boards, which are now 42% women (FTSE Women Leaders Review 2024). But board representation has not resulted in the same progress in executive committees where women hold just 30% of roles.

The barrier for women entering the C-suite (the top management positions in a company) has been termed the ‘glass ceiling’. Why does it exist and what can be done about it?

The business case for women CEOs

Firms with women CEOs perform better, according to research conducted by consultancies and financial institutions, but these results are not rigorous (Jeong and Harrison, 2017; Edmans, 2018).

Peer-reviewed meta-analyses, across countries, have found a statistically significant positive correlation between women CEOs and business performance. But in real terms, this effect is very small (Pletzer et al, 2015; Post and Bryan, 2015).

In other words, women CEOs do not drastically improve a company’s bottom line. But equally, they do not damage it. If gender has little effect on a company’s performance, why are so few women in the top jobs?

Why are there so few women CEOs?

Prejudice

One potential reason for the lack of women CEOs is the stereotype that men are innately better suited to the position. Prejudicial ideas about women can result in discriminatory behaviour in the workplace and can be disadvantageous to women when hiring decisions are made.

Society has pre-set ideas about the traits of men and women. For example, stereotypical feminine traits include empathy, kindness and loyalty, whereas stereotypical masculine traits include competence, competitiveness and dominance (Heilman, 2012). These masculine traits are positively associated with leadership.

What’s more, when women exhibit masculine traits, they are perceived differently to men (Eagly and Carli, 2007). Assertiveness is viewed as a positive attribute for a man, but a negative one for a woman unless she can also demonstrate the expected communal behaviour of women (Heilman and Okimoto, 2007).

When women CEOs express anger, their competence is downgraded. But for men, perceived competence either increases or remains the same (Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). This suggests that ‘androcentrism’ is at play in the corporate world, with the masculine viewpoint being made central (Bailey et al, 2020).

The ‘double bind’ expresses the idea that women must walk a fine line, exhibiting opposing traits simultaneously. They are expected to be feminine but not too feminine in dress, language and tone of voice (Oakley, 2000).

Women face a catch-22. If they adopt a typically masculine linguistic style, they can be seen as aggressive, but if they are too feminine, they risk lacking authority (Coates, 2015).

A gender confidence gap

Research reveals that women are more likely to shy away from promotion competitions due to different attitudes to competition and confidence levels compared with men (Niederle and Vesterlund 2011).

Underconfidence can result in women opting out of competition for more senior roles. Among holders of MBAs (a standard postgraduate qualification in business), 12% of women aspired to boardroom positions five years after graduation compared with 22% of men (Weiser, 2021).

This gender confidence gap is created early in life, through social expectations, experience and culture. A lack of confidence results in evaluators forming overly pessimistic beliefs about women (Exley and Nielsen, 2024). This creates a vicious cycle, as women can internalise this pessimism and become less confident.

Networks

In 2023, 77% of new CEO appointments were internal hires (Forsdick, 2024). Boards and CEO selection committees favour candidates whom they know and who have intimate knowledge of the company.

This practice increases trust between the CEO and the board, as exhibited by reduced board monitoring when there are network ties (Fracassi and Tate, 2012). These ties include serving on the same charity boards, graduating from the same university and playing golf at the same clubs.

Women are less likely to receive work-related help from their informal networks (McGuire, 2002). One example from popular culture that highlighting this phenomenon is in the American sitcom Friends when Rachel takes up smoking so she won’t miss business discussions taking place during cigarette breaks: she earns a promotion as a result.

Type-based mentoring matches low-level employees with seniors who are like them in gender and race. This mechanism mimics natural social networks in which people tend to communicate better when they have common interests and experiences (Athey et al, 2000).

Most senior leaders are men, so there are fewer women mentors. As a result, women do not gain the same human capital that mentoring provides. The exclusion of women from informal networks can explain in part why most CEOs are still white men.

Pipeline: commercial versus functional roles

The traditional pathway to the C-suite is completing a business-related degree, which are dominated by men, followed by an MBA programme (Murray, 2023). Women that complete this pathway often end up in functional roles, namely human resources (HR) and marketing, while CEOs are selected from commercial roles (Pipeline, 2023).

Women account for 71% of HR workers, in part due to the idea that women possess the soft skills needed in these roles. In addition, in the workplace, women carry out more work that is defined as ‘non-promotable’. These can include training new hires, taking notes in meetings or even organising the office party (Weingart et al, 2022).

The motherhood penalty

Women aged 16-24 account for around 50% of managers. But as they enter the most common ages of childbearing (between 25 and 44), this share falls and never fully recovers.

Having children is delaying or stopping women’s career progress, but why?

Figure 2: Proportion of women in managerial positions in the UK by age

Source: Proportion of women in managerial positions, UK, 2012 to 2022, Office for National Statistics (ONS)

Having children affects women’s earnings but not men’s earnings (Kleven et al, 2019, 2023). The earnings gap can in part be attributed to career interruption and differences in hours worked (Bertrand et al, 2009).

These differences occur as women provide the majority of unpaid labour, including childcare, housework and care for other family members. This extra labour results in women being less flexible employees.

The 2023 economics Nobel laureate Claudia Goldin shows that the ascendency of male workers to seniority is rooted in long hours and constant availability (Goldin, 2014). Motherhood restricts women from this working style.

Figure 3: Average hours of unpaid work done per week by age and gender in UK in 2015

Source: Harmonised European time use survey, UK, 2015, ONS

Figure 4: Percentage of employed 16-64-year-olds who were in full-time and part-time employment, by gender

Source: Full-time and part-time employment, UK, 2023, ONS

Further, women are less likely to be hired if there is an expectation that they will take maternity leave (Booth, 2023). There is a prejudice that women who take time to have children are less committed to their careers or are less dependable employees (Arena et al, 2022).

This prejudice results in a lack of investment in women of childbearing age, creating a gap in the pipeline for women CEOs.

What can be done to address the problem?

Both businesses and government can take steps to help to reduce this gap.

Combating the motherhood penalty

The UK government is making the largest investment in childcare in history. Reducing the cost of childcare gives women the choice to return to work sooner, reducing the human capital lost (Casarico, 2023).

Yet monetary intervention alone is not enough. In Denmark and South Korea, for example, the motherhood penalty persists in spite of expansive monetary intervention (Kliff, 2018). Challenging the underlying prejudices and adopting flexible working practices can have a positive impact in combating maternity bias too (Fox and Quinn, 2015).

From the board to the C-suite

Increasing the number of women on company boards has a positive effect on the number of women in the executive suite (Matsa and Miller, 2011). Women help women in various ways, including hiring preferences, changing company culture and acting as role models.

The UK has taken a voluntary approach to increasing the number of women on boards, whereas some European countries have set formal quotas.

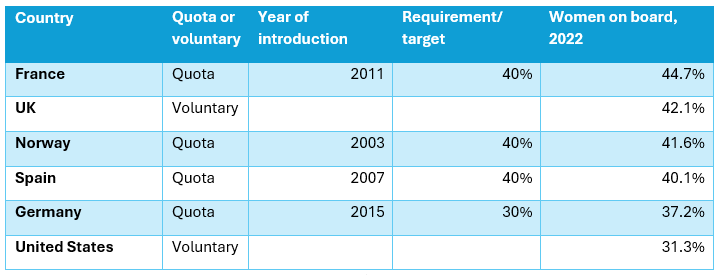

Table 1: Quotas mandating board membership of women

Source: Female share of seats on boards of largest publicly listed companies 2010-2022, OECD; quota summaries available from FTSE Women Leaders Review 2024.

The UK’s approach involved funding three independent reports into women in the FTSE 100 companies. Visibility of the issue has nudged industry into action, and the UK is performing at a similar level to countries with set quotas.

Figure 5: Women’s share of seats on the boards of the largest publicly listed companies in advanced countries (%)

Source: Female share of seats on boards of largest publicly listed companies 2010-2022, OECD

The FTSE Women Leaders Review 2024 reveals that 40% of new executive appointments are going to women (FTSE Women Leaders Review, 2024). More women are entering the industry, normalising their leadership. While gender equity among CEOs is a long way off – an estimated 76 years – progress is being made (McCulloch, 2023).

Where can I find out more?

- Why there are so few women CEOs?: Vanessa Fuhrmans on the Journal podcast.

- The no club by Laurie Weingart, Lise Vesterlund, Brenda Peyser and Linda Babcock.

- Women and the labyrinth of leadership by Alice Eagly and Linda Carli.

Who are experts on this question?

- Marianne Bertrand

- Alex Edmans