With coronavirus entering a dangerous phase and winter approaching, the outlook for the Scottish economy has never been more uncertain. Many jobs remain furloughed, working hours have fallen sharply, and activity in the services sector is below where it was a decade ago.

As in other parts of the UK, cases of Covid-19 have been on the increase in Scotland in recent weeks. In response, on Friday 23 October, Scotland’s First Minister announced a new five tier framework for managing restrictions at a local level to tackle the virus. Different parts of the country will be placed into different tiers, with the new system coming into effect from Monday 2 November.

Figure 1: Confirmed new Covid-19 cases

Source: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/cases

One of the interesting public policy features of this crisis in the UK has been that policy responsibilities for managing the public health and economic response have been split across devolved and national government – see: What are the implications of coronavirus for fiscal devolution in the UK?

Just how well has the Scottish economy been coping with the effects of Covid-19 and is there any evidence – so far- of any apparent divergence in economic outcomes with the rest of the UK?

Economic performance since March

Scotland entered lockdown like the rest of the UK on 23 March – for a timeline of the various policy announcements in Scotland, see this information sheet on the Scottish Parliament’s website.

With public health devolved, it has been up to the Scottish government to set out any phasing in the lifting of restrictions. In May, the Scottish government published a route-map setting out their approach, with the new tiered system announced in October the replacement for the next few months.

On the whole, perceptions are that the easing of restrictions in Scotland – at least at the margin – have proceeded slightly more cautiously than in the UK as a whole. There is some evidence for this, for example construction firms were able to return to sites 2-3 weeks later than in England. But in the main, on the major policy choices such as the closure and re-opening of schools, there has been relative alignment.

We have the advantage in Scotland of having a broader suite of economic statistics to look at than other devolved nations and regions of the UK.

For example, at the onset of the crisis, the Scottish government started to publish a monthly GVA (gross value added) series and a monthly turnover index to provide more real-time information on how the economy was tracking.

What do they show?

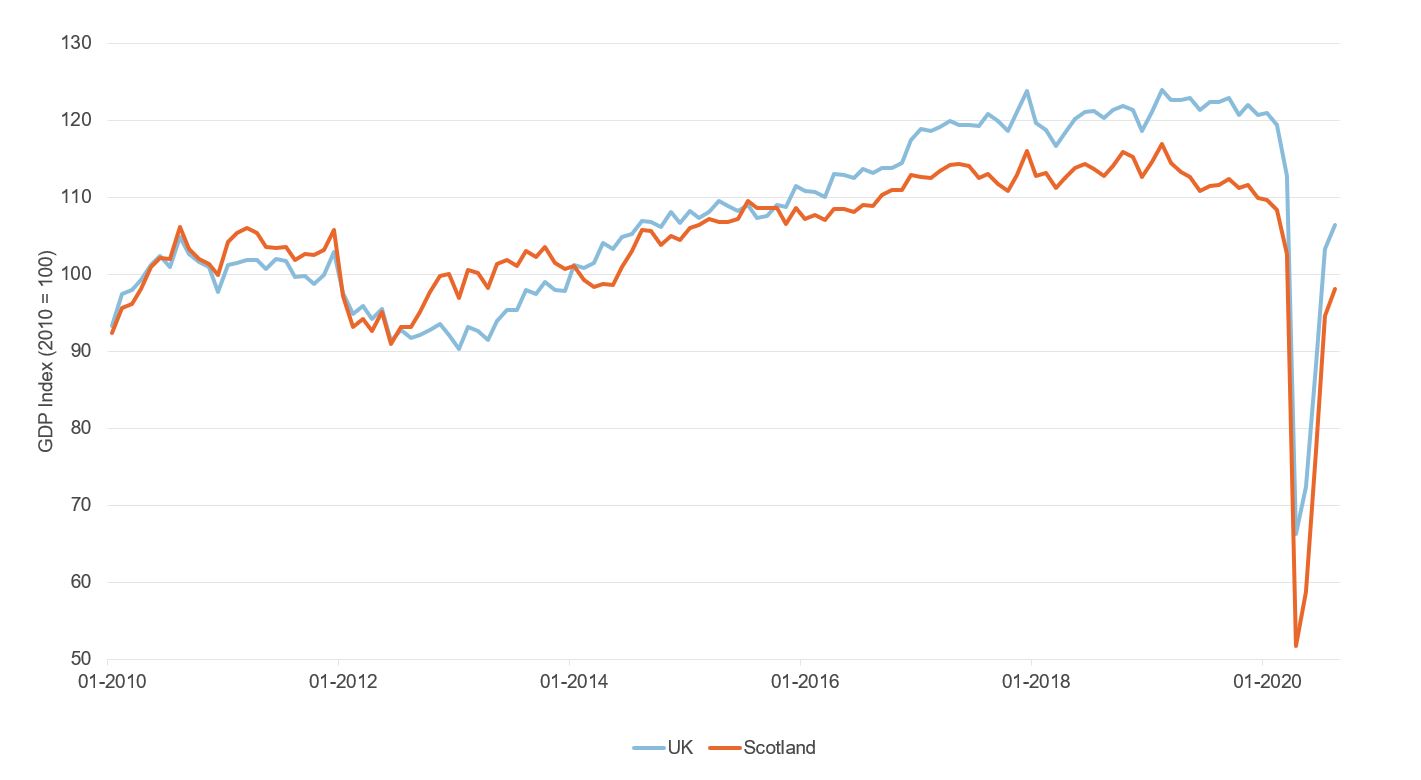

Scottish economic activity fell 21.7% between February and April, which compare to a fall of 23.3% in the UK as a whole (see Figure 2).

The latest data suggest that by August, economic activity had grown by 16% since May, but remained over 9% below its pre-lockdown level in February.

Figure 2: Monthly GDP

Source: ONS and Scottish Government

Of course, these aggregate numbers disguise the significant variations in economic experience people are having at this time.

Even on a sector level, we see huge variations in levels of economic activity.

In accommodation and food services (see Figure 3), in the services sector as a whole (see Figure 4) and in the construction sector (see Figure 5), activity remains well below its level earlier in 2020.

Activity in the services sector in the UK as a whole is now where it was in 2014. In Scotland, it’s below where it was a decade ago.

Figure 3: Scottish monthly GDP in the accommodation and food services sector

Source: Scottish Government

Figure 4: Monthly GDP in the services sector

Source: ONS and Scottish Government

Figure 5: UK and Scottish monthly GDP in the construction sector

Source: ONS and Scottish Government

On the labour market, like the rest of the UK, the furlough scheme has helped to cushion any immediate increase in unemployment in Scotland. But new experimental data from HMRC suggest that Scotland might have seen the biggest fall in PAYE workers outside of London (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: PAYE employment

Source: HMRC

At its peak around 780,000 jobs in Scotland were furloughed under the UK government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) – 32% of the workforce.

This number has now fallen back and as Figure 7 illustrates, since the beginning of July, the share of jobs furloughed in Scotland has fallen faster than in the other nations of the UK.

Figure 7: Jobs furloughed under the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme

Source: UK Government

But many jobs remain furloughed. Even by August, around 240,000 jobs in Scotland were still on furlough.

Like the rest of the UK, the big change has been in working hours, which have fallen sharply (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Hours worked

Source: ONS, Labour Force Survey and Annual Population Survey

The Scottish data are not available on a quarterly basis to the second quarter of 2020 like the UK data. Instead, they cover the year up until the end of June 2020. That is why this measure is not dropping by as much as the measure for the UK as a whole (one way to see what this means is to recognise that that the Scottish measure is essentially ‘averaging’ over three good quarters (the last two quarters of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020) and one bad quarter (the second quarter of 2020).

The policy response

While most of the public health policy levers – including indirect levers such as the opening and closing of schools – are controlled by the Scottish government, most of the key economic policy support levers are held by the UK government.

The Scottish government has implemented a range of support packages, such as business rates holidays and business support grants. These have largely been consistent with the same measures announced for the UK as a whole, but repackaged for a Scottish business base and funded by ‘Barnett consequentials’ from equivalent programmes in England.

The Scottish government’s primary economic policy focus has therefore been on the recovery and rebuilding the economy over time. In June, the Scottish government published the recommendations of an Economic Recovery Advisory Board. Reaction was mixed, with the report full of big ideas but more limited practical options for immediate impact.

Like the rest of the UK, relations between the business community and the Scottish government have been increasingly strained in recent times.

More broadly, there have been controversies between the Scottish and UK governments over the allocation of funding and the ability of the Scottish government (and the other devolved governments) to have greater flexibility over the overall spending envelope that they have.

What next?

With the virus entering a dangerous next phase, the outlook for the Scottish economy looks challenging.

With the Scottish winter just weeks away, sectors such as hospitality and tourism face a bleak and worrisome few months. With many of these sectors employing those on lower earnings, there is a risk of a rise in inequalities. The most recent Fraser of Allander Economic Commentary suggests that there has never been a more uncertain outlook for Scotland in living memory.

On the whole, the experience of Scotland during the Covid-19 economic crisis has broadly mirrored that of the UK as a whole. Time will tell how our economies cope with the next phase of this pandemic.

Where can I find out more?

- The Fraser of Allander Institute at the University of Strathclyde publishes regular reports on fiscal and economic issues in Scotland.

- The Scottish government’s Key economic statistics brings together monthly data covering topics such as employment, indices, exports and earnings.

Who are experts on this question?

- Graeme Roy, Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde

- Stuart McIntyre, Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde

- David Bell, University of Stirling